Content from Перед тим як почати

Last updated on 2026-01-19 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

- Основна мета цього епізоду - допомогти слухачам комфортно почуватися під час користування інтерфейсом RStudio.

- У епізоді “Початкове налаштування” виконуйте усі етапи дуже

повільно. Переконайтеся, що всі учасники встигають за ходом заняття

(нагадайте їм користуватися наліпками для зворотного зв’язку). На цьому

етапі домовтеся з помічниками, щоб вони ходили по аудиторії та

допомагали учасникам. Дуже важливо впевнитися, що всі працюють у

правильному робочому каталозі та створили підкаталог

data(усі літери малі).

Overview

Questions

- Як орієнтуватися в RStudio?

- Як взаємодіяти з R?

- Як керувати робочим середовищем?

- Як встановити пакети?

Objectives

- Встановити останню версію R.

- Встановити останню версію RStudio.

- Ознайомитися з інтерфейсом RStudio.

- Встановити додаткові пакети за допомогою вкладки “packages”.

- Встановити додаткові пакети за допомогою команд R.

Що таке R? Що таке RStudio?

Термін “R” використовується як для позначення мови

програмування, так і для програмного забезпечення, яке виконує скрипти,

написані цією мовою.

RStudio нині є дуже популярним середовищем не тільки для написання скриптів на R, але й взаємодії з програмним забезпеченням R. Для правильної роботи RStudio потребує R і тому обидва необхідно встановити на ваш комп’ютер.

Щоб полегшити роботу з R, ми будемо використовувати RStudio. RStudio є найпопулярнішим IDE (інтегроване середовище розробки) для R. IDE - це частина програмного забезпечення, яка надає інструменти для полегшення програмування.

Також ви можете використовувати функцію R Presentations, щоб представляти свою роботу у вигляді презентації HTML5, поєднуючи Markdown і код на R. Ви можете переглядати їх безпосередньо в R Studio або у браузері. Є багато варіантів налаштування слайдів презентації, зокрема можливість зображати рівняння у форматі LaTeX. Це може допомогти вам співпрацювати з іншими, а також застосовувати для викладання та використання в класі.

Навіщо вивчати R?

У R не потрібно багато клацати мишкою — і це добре

Крива навчання може бути крутішою, ніж в інших програм, але в R результати аналізу залежать не від того, чи ви запам’ятали послідовність клацань мишкою, а від написаних команд — і це добре! Тому, якщо ви хочете повторити аналіз після того, як зібрали більше даних, вам не потрібно згадувати, у якому порядку ви натискали кнопки, щоб отримати результат — достатньо просто знову запустити свій скрипт.

Робота зі скриптами робить кроки вашого аналізу зрозумілими, а написаний вами код може переглянути інша людина, щоб дати відгук і помітити помилки.

Робота зі скриптами змушує вас глибше розуміти те, що ви робите, і допомагає краще вивчати та усвідомлювати методи, які ви використовуєте.

Код R сприяє відтворюваності

Відтворюваність — це коли інша людина (або навіть ви в майбутньому) може отримати ті самі результати з того самого набору даних, використовуючи той самий аналіз.

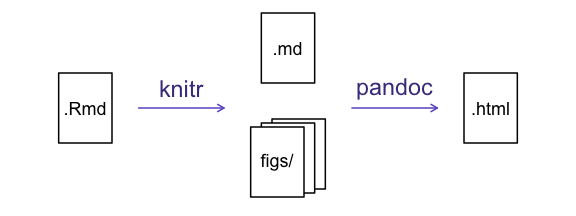

R інтегрується з іншими інструментами, щоб створювати публікації прямо з вашого коду. Якщо ви зберете більше даних або виправите помилку в наборі даних, графіки та статистичні тести у вашому документі оновляться автоматично.

Все більше журналів і грантодавців очікують, що аналізи будуть відтворюваними, тож знання R дає вам перевагу для виконання цих вимог.

Щоб ще більше підтримати відтворюваність і прозорість, існують пакети, які допомагають керувати залежностями: відстежувати, які пакети ми завантажуємо і як вони залежать від версії пакета, яку ви використовуєте. Це допомагає переконатися, що наявні робочі процеси працюють стабільно й продовжують виконувати те саме, що й раніше.

Такі пакети, як renv, дозволяють “зберігати” й “завантажувати” стан бібліотеки вашого проєкту, а також відстежують версії пакетів, які ви використовуєте, і джерело, з якого їх можна отримати.

R є міждисциплінарним і розширюваним

Маючи понад 10,000+ пакетів, які можна встановити для розширення її можливостей, R забезпечує середовище, що дозволяє поєднувати статистичні підходи з різних наукових дисциплін і підібрати саме ту аналітичну структуру, яка найкраще підходить для аналізу ваших даних. Наприклад, у R є пакети для аналізу зображень, GIS, часових рядів, популяційної генетики та багато іншого.

R працює з даними будь-яких форм і розмірів

Навички, які ви здобуваєте в R, легко масштабуються разом із розміром вашого набору даних. Незалежно від того, чи має ваш набір даних сотні чи мільйони рядків, це не матиме особливого значення для вас.

R призначений для аналізу даних. У R є спеціальні структури даних і типи даних, які роблять роботу з пропущеними значеннями та статистичними факторами зручною.

R може підключатися до електронних таблиць, баз даних та багатьох інших форматів даних — як на вашому комп’ютері, так і в інтернеті.

R створює високоякісну графіку

Можливості побудови графіків у R практично безмежні й дозволяють налаштувати будь-який аспект графіка, щоб якнайкраще передати зміст ваших даних.

R має велику та привітну спільноту

Тисячі людей використовують R щодня. Багато з них готові допомогти вам через списки розсилки та вебсайти, такі як Stack Overflow, або на спільноті RStudio. Питання, які супроводжуються короткими, відтворюваними фрагментами коду, швидше за все, отримують компетентні відповіді.

R не лише безплатна, вона також є з відкритим кодом і працює на різних операційних системах

Кожен може переглянути вихідний код, щоб побачити, як працює R. Завдяки такій прозорості менше шансів на помилки, а якщо ви (або хтось інший) їх знайдете — можна повідомити про них і виправити.

Оскільки R є відкритим кодом і підтримується великою спільнотою розробників та користувачів, існує дуже великий вибір сторонніх додаткових пакетів, які безплатно розширюють базові можливості R.

RStudio розширює можливості R та спрощує написання коду і взаємодію з R. Автор фото зліва; Автор фото справа.

Огляд RStudio

Знайомство з RStudio

Почнемо з вивчення RStudio, який є інтегрованим середовищем розробки (IDE) для роботи з R.

Відкрита версія RStudio IDE є безплатною за Загальна публічна ліцензія Affero (AGPL) v3. RStudio IDE також доступна з комерційною ліцензією та пріоритетною email-підтримкою від RStudio, Inc.

Ми будемо використовувати RStudio IDE для написання коду, роботи з файлами на комп’ютері, перегляду створених змінних і візуалізації побудованих графіків. RStudio також можна використовувати для інших речей (наприклад, контролю версій, розробки пакетів, створення Shiny-застосунків), які ми не розглядатимемо під час цього курсу.

Однією з переваг використання RStudio є те, що вся інформація, необхідна для написання коду, доступна в одному вікні. Крім того, RStudio надає багато комбінацій клавіш, автодоповнення та підсвічування синтаксису для основних типів файлів, які ви використовуєте під час роботи в R. RStudio робить набір коду простішим і менш схильним до помилок.

Налаштування

Це хороша практика зберегти набір пов’язаних даних, аналіз і текст самою текою під назвою робочий каталог. Усі скрипти у цій теці можуть потім використовувати відносні шляхи до файлів. Відносні шляхи вказують, де саме всередині проєкту знаходиться файл (на відміну від абсолютних шляхів, які показують розташування файлу на конкретному комп’ютері). Такий спосіб роботи значно полегшує перенесення вашого проєкту на інший комп’ютер або обмін ним з іншими, без потреби змінювати шляхи до файлів у кожному окремому скрипті.

RStudio надає зручні інструменти для цього через інтерфейс “Проєкти”, який не лише створює для вас робочий каталог, але й запам’ятовує її розташування (що дозволяє швидко повертатися до неї). Цей інтерфейс також (за бажанням) зберігає ваші налаштування та відкриті файли, щоб вам було легше продовжити роботу після перерви.

Створення нового проєкту

- У меню

File(файл) натиснітьNew project(новий проєкт), виберітьNew directory(новий каталог), потімNew project(новий проєкт) - Введіть назву цієї нової теки (або “каталогу”) і виберіть зручне

розташування для неї. Це буде ваш робочий каталог до

кінця дня (наприклад,

~/data-carpentry) - Натисніть

Create project(створити проєкт) - Створіть новий файл, у якому ми будемо писати наші скрипти.

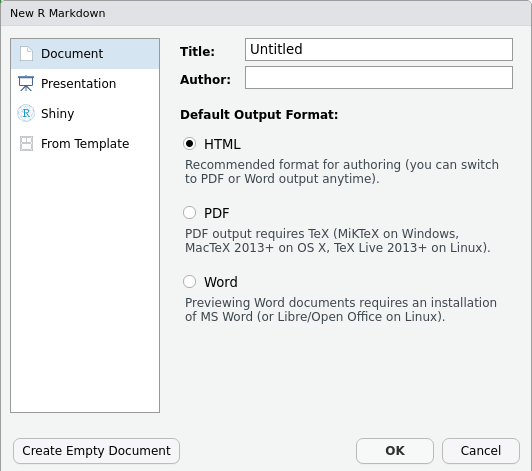

Перейдіть до File (файл) > New File (новий файл) > R script

(скрипт R). Натисніть значок збереження на панелі інструментів і

збережіть ваш скрипт як “

script.R”.

Найпростіший спосіб відкрити проєкт RStudio після його створення - це

перейти до теки, де збережено проєкт і двічі клацнути на файлі

.Rproj (синій куб). Це відкриє RStudio і запустить вашу

сесію R у тому самому каталозі, де знаходиться файл

.Rproj. Усі ваші дані, графіки та скрипти тепер будуть

відносними до каталогу проєкт. Проєкти RStudio мають додаткову перевагу:

вони дозволяють відкривати кілька проєктів одночасно, кожен у власному

каталозі проєкту. Це дозволяє тримати відкритими кілька проєктів

одночасно, не заважаючи один одному.

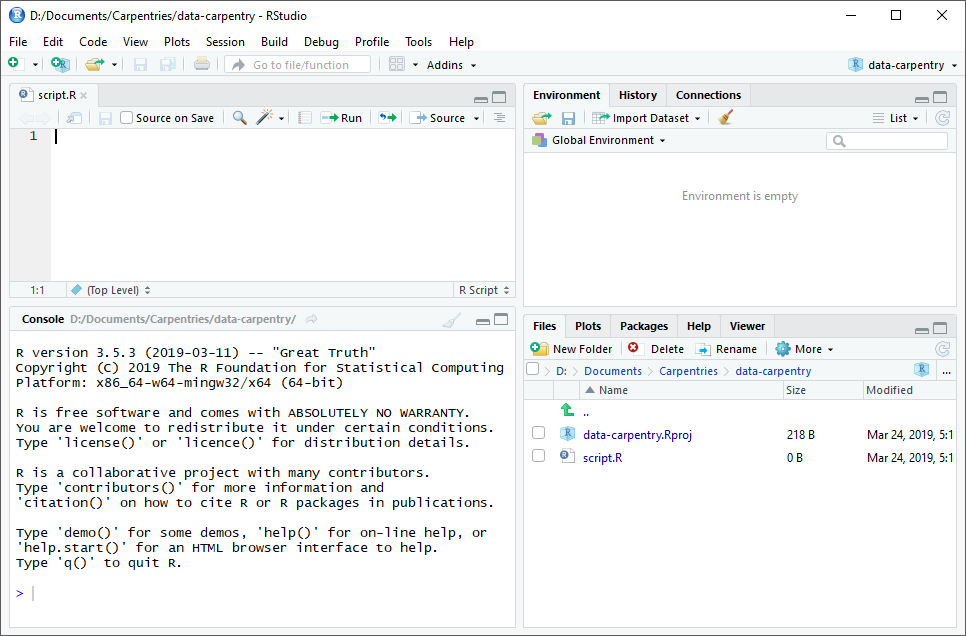

Інтерфейс RStudio

Давайте швидко ознайомимося з RStudio.

RStudio поділено на чотири “панелі”. Розміщення цих панелей та їх вміст можна налаштувати (див. меню, Tools (Інструменти) -> Global Options (Глобальні параметри) -> Pane Layout (Макет панелі)).

Макет за замовчуванням:

- Ліворуч вгорі - Source: ваші скрипти та документи

- Ліворуч унизу - Console: як виглядав би R без RStudio

- Праворуч угорі - Environment/History: тут можна побачити, що ви зробили

- Праворуч унизу - Files і інші вкладки: тут можна переглядати вміст проєкту/робочого каталогу, наприклад ваш файл Script.R

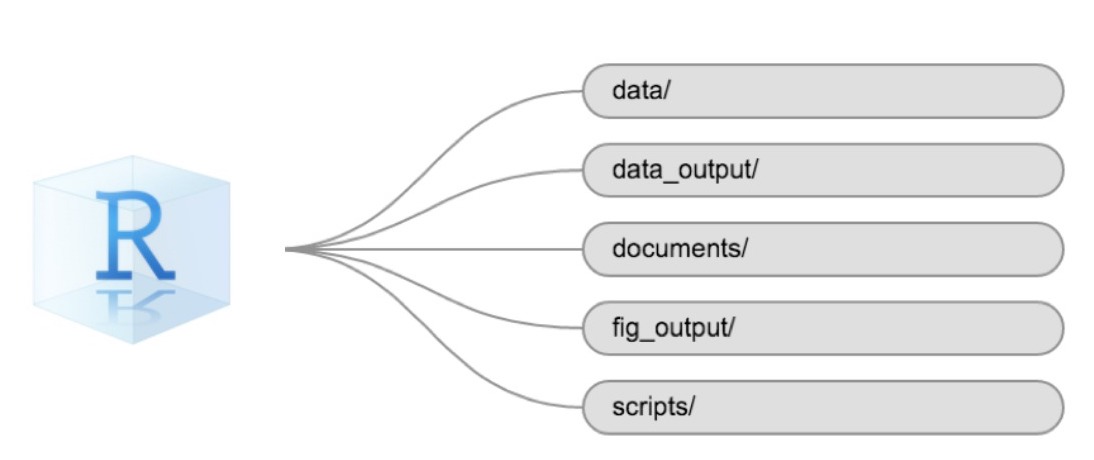

Організація робочого каталогу

Використання послідовної структури тек у всіх ваших проєктах допоможе підтримувати порядок і полегшить знаходження та збереження файлів у майбутньому. Це може бути особливо корисним, коли у вас є кілька проєктів. Загалом, ви можете створити каталоги (теки) для скриптів, даних та документів. Ось - кілька прикладів запропонованих каталогів:

-

data/Використовуйте цю теку для зберігання необроблених даних та проміжних наборів даних. З метою прозорості та походження, ви повинні завжди зберігати копію ваших необроблених даних доступною та максимально виконувати очищення й попередню обробку даних програмно (тобто за допомогою скриптів, а не вручну), наскільки це можливо. -

data_output/Коли вам потрібно змінити необроблені дані, може бути корисно зберігати змінені версії наборів даних в іншій теці. -

documents/Використовується для контурів, чернеток та іншого тексту. -

fig_output/Ця тека може зберігати графіку, створену вашими скриптами. -

scripts/Місце для зберігання ваших R-скриптів для різних аналізів або побудови графіків.

Вам можуть знадобитися додаткові каталоги або підкаталоги залежно від потреб вашого проєкту, але вони повинні складати основу вашого робочого каталогу.

Робочий каталог

Робочий каталог - важливе поняття для розуміння. Це місце, де R буде шукати та зберігати файли. Коли ви пишете код для свого проєкту, ваші скрипти повинні посилатися на файли відносно кореня робочої директорії й лише на файли в межах цієї структури.

Використання проєктів RStudio полегшує роботу і гарантує належне

налаштування робочого каталогу. Якщо вам потрібно перевірити це, ви

можете використовувати getwd (). Якщо з якоїсь причини ваш

робочий каталог не збігається з місцем розташування вашого проєкту

RStudio, ймовірно, ви відкрили R-скрипт або файл RMarkDown

не ваш файл .Rproj. Вам необхідно закрити

RStudio і відкрити файл .Rproj, двічі клацнувши на синьому

кубі! Якщо вам коли-небудь потрібно змінити робочий каталог у скрипті,

setwd ('my/path') змінює робочий каталог. Це слід

використовувати обережно, оскільки такий підхід ускладнює обмін аналізом

між різними пристроями та іншими користувачами.

Завантаження даних та налаштування

Для цього уроку ми будемо використовувати такі теки в нашому робочому

каталозі: data/,

data_output/ та

fig_output/. Давайте послідовно запишемо

все з малих літер. Ми можемо створити їх через інтерфейс RStudio,

натиснувши кнопку “New Folder” у панелі файлів (справа внизу), або

безпосередньо в R, ввівши в консолі:

R

dir.create("data")

dir.create("data_output")

dir.create("fig_output")

Ви можете завантажити дані, використані для цього уроку, з GitHub або

за допомогою R. Ви можете скопіювати дані з цього посилання

GitHub і вставити їх у файл під назвою Safi_clean.csv у

каталозі data/, який ви щойно створили. Або ви можете

зробити це безпосередньо в R, скопіювавши та вставивши це у свій

термінал (викладач може розмістити цей фрагмент коду в Etherpad):

R

download.file("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datacarpentry/r-socialsci/main/episodes/data/SAFI_clean.csv","data/SAFI_clean.csv", mode = "wb")

Взаємодія з R

Основою програмування є те, що ми записуємо інструкції, які комп’ютер має виконати, а потім даємо йому команду їх виконати. Ми записуємо або кодуємо інструкції в R, тому що це спільна мова, яку розуміє і комп’ютер, і ми. Ми називаємо ці інструкції командами і просимо комп’ютер виконати їх, тобто виконати (або запустити) ці команди.

Існує два основних способи взаємодії з R: за допомогою консолі або за допомогою файлів скриптів (звичайних текстових файлів, які містять ваш код). Консоль (у RStudio — це нижня ліва панель) — це місце, де можна вводити команди мовою R і комп’ютер одразу їх виконає. Це також місце, де будуть показані результати виконаних команд. Ви можете ввести команди безпосередньо в консоль і натиснути Enter, щоб виконати їх, але вони будуть втрачені, щойно ви закриєте сесію.

Оскільки ми хочемо, щоб наш код і робочий процес були відтворюваними, краще вводити потрібні команди в редактор скриптів і зберігати цей скрипт. Таким чином у нас залишається повний запис того, що ми зробили й будь-хто (включно з нами в майбутньому!) зможуть легко відтворити результати на своєму комп’ютері.

RStudio дозволяє виконувати команди прямо з редактора скриптів за допомогою комбінації клавіш Ctrl + Enter (на Mac, Cmd + Return). Команда на поточному рядку в скрипті (позначена курсором) або всі команди в виділеному тексті будуть надіслані на консоль і виконані при натисканні Ctrl + Enter. Якщо в консолі є інформація, яка вам більше не потрібна, ви можете очистити її за допомогою Ctrl + L. Ви можете знайти інші комбінації клавіш у цій шпаргалці RStudio про RStudio IDE.

На певному етапі аналізу ви можете перевірити вміст змінної або структуру об’єкта без необхідності збереження запису в вашому скрипті. Ви можете ввести ці команди та виконати їх безпосередньо в консолі. RStudio надає комбінації клавіш Ctrl + 1 та Ctrl + 2, що дозволяють переходити між скриптом і консоллю.

Якщо R готовий приймати команди, консоль R показує >.

Якщо R отримає команду (шляхом введення, копіювання-вставлення або

надіслану з редактора скриптів за допомогою Ctrl +

Enter), R спробує виконати її й коли буде готовий, покаже

результати та знову виведе новий >, щоб чекати на

наступні команди.

Якщо R все ще чекає, коли ви введете більше тексту, консоль покаже

+. Це означає, що ви не закінчили введення повної команди.

Ймовірно, це пов’язано з тим, що ви не ‘закрили’ дужки або цитату, тобто

у вас немає такої ж кількості лівих дужок, як правих дужок, або такої ж

кількості початкових та закритих лапок. Якщо таке трапляється, а ви

думали, що закінчили вводити команду, натисніть у вікні консолі та

натисніть Esc; це скасує незавершену команду та поверне вас

до запиту >. Потім ви можете коригувати введену команду

та виправити помилку.

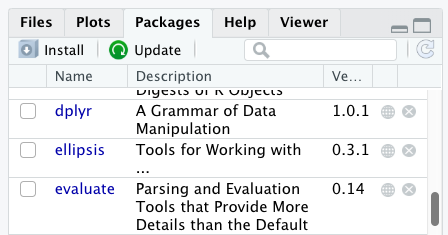

Встановлення додаткових пакетів за допомогою вкладки “пакети”

На додаток до базової інсталяції R, існує понад 10,000 додаткових пакетів, які можуть бути використані для розширення функціональності R. Багато з них були написані користувачами R і були доступні в центральних репозиторіях, який розміщений на CRAN, щоб кожен міг завантажити та встановити їх у власне середовище R. У вас вже має бути встановлено пакети ‘ggplot2’ та ’dplyr. Якщо ви цього не зробили, будь ласка, зробіть це зараз, використовуючи ці інструкції.

Ви можете перевірити, чи встановлений у вас пакет, переглянувши

вкладку packages (за замовчуванням внизу праворуч). Ви

також можете ввести команду installed.packages()в консоль і

перевірити вивід.

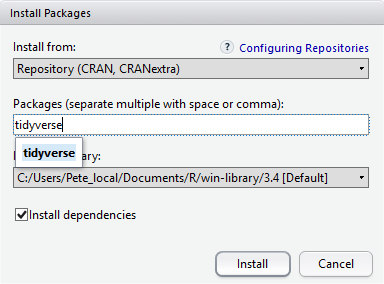

Додаткові пакети можна встановити із вкладки ‘packages’. На вкладці пакетів натисніть значок ‘Install’ (Встановити) і почніть вводити назву потрібного пакета у текстовому полі. Під час введення тексту пакети, назви яких починаються з введених вами символів, будуть показуватися у випадному списку і ви зможете вибрати потрібний.

У нижній частині вікна Install Packages (Встановити пакети) є прапорець ‘Install’ dependencies (Встановити залежності). Цю опцію за замовчуванням увімкнено, і зазвичай саме так і потрібно. Пакети можуть (і справді) використовувати функціональність, вбудовану в інші пакети, тому для того, щоб функції пакета, який ви встановлюєте, працювали правильно, може знадобитися встановлення інших пакетів разом із ним. Опція ‘Install dependencies’ (встановити залежності) забезпечує, щоб ці додаткові пакети також були встановлені.

Завдання

Використовуйте вкладку Console (Консоль) і Packages (Пакети), щоб переконатися, що у вас встановлено tidyverse.

Прокрутіть вкладку пакетів вниз до ‘tidyverse’. Ви також можете ввести кілька символів у вікно пошуку. Пакет ‘tidyverse’ насправді є набором пакетів, включаючи ‘ggplot2’ та ‘dplyr’, які обидва потребують інших пакетів для коректної роботи. Всі ці пакети будуть встановлені автоматично. Залежно від того, які пакети раніше були встановлені у вашому середовищі R, встановлення ‘tidyverse’ може бути дуже швидким або ж зайняти кілька хвилин. Під час встановлення на консолі будуть виводитися повідомлення, пов’язані з прогресом його виконання. Ви зможете побачити всі пакети, які фактично встановлюються.

Оскільки процес встановлення отримує доступ до сховища CRAN, вам знадобиться підключення до Інтернету для встановлення пакетів.

Також можна встановити пакети з інших репозиторіїв, в тому числі з Github або локальної файлової системи, але ми не будемо розглядати ці варіанти в цьому уроці.

Встановлення додаткових пакетів за допомогою команд R

Якщо ви дивилися вікно консолі під час запуску встановлення ‘tidyverse’, можливо, ви помітили, що рядок

R

install.packages("tidyverse")

був записаний на консоль до початку інсталяційних повідомлень.

Ви також могли встановити пакети

tidyverse, виконавши цю команду

безпосередньо в терміналі R.

Ми будемо використовувати ще один пакет під назвою

here протягом усього курсу для керування

шляхами та каталогами. Ми обговоримо це більш детально в пізньому

епізоді, але зараз ми встановимо його в консолі:

R

install.packages("here")

- Використовуйте RStudio для створення та запуску програм R.

- Використовуйте

install.packages()для встановлення пакетів (бібліотек).

Content from Введення до R

Last updated on 2026-01-17 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 80 minutes

- Основна мета - познайомити користувачів з різними об’єктами в R, від елементарних типів до створення власних об’єктів.

- Хоча цей розділ є базовим, будьте обережні, щоб не “загрузнути в деталях”, адже різноманіття типів і операцій може бути надто складним для новачків — особливо до того, як вони зрозуміють, як усе це вписується у їх власний “робочий процес”.

Overview

Questions

- Які типи даних доступні в R?

- Що таке об’єкт?

- Як можна присвоювати іменам об’єкти різних типів даних?

- Які арифметичні та логічні оператори можна використовувати?

- Як можна отримати підмножини з векторів?

- Як в R трактувати відсутні значення?

- Як ми можемо впоратися з відсутніми значеннями в R?

Objectives

- Визначити такі терміни, як вони стосуються R: об’єкт, призначення, виклик, функція, аргументи, параметри.

- Призначити значення іменам у R.

- Дізнатися, як називати об’єкти.

- Використовувати коментарі для інформування сценарію.

- Розв’язувати прості арифметичні операції в R.

- Викликати функції та використовувати аргументи, щоб змінити їх параметри за замовчуванням.

- Оглянути вміст векторів і маніпулювати їх вмістом.

- Значення підмножини з векторів.

- Аналізувати вектори з відсутніми даними.

Створення об’єктів в R

Ви можете використовувати R для простих математичних обчислень, друкуючи формули у консолі:

R

3 + 5

OUTPUT

[1] 8R

12 / 7

OUTPUT

[1] 1.714286Все, що існує в R - це об’єкти: від простих числових

значень та рядків до складніших об’єктів, таких як вектори, матриці та

списки. Навіть вирази й функції є об’єктами в R.

Однак, щоб робити корисні та цікаві речі, нам потрібно звертатися до

об’єктів. Для цього нам потрібно вказати ім’я, за яким слідує

оператор присвоєння <-, і об’єкт, який ми

хочемо назвати:

R

areaHectares <- 1.0

<- - оператор присвоєння. Він призначає значення

(об’єкти) праворуч іменам (також званим символами) на ліворуч.

Отже, після виконання x <- 3 значення x

дорівнює 3. Стрілку можна прочитати як 3 переходить

в x. З історичних причин ви також можете

використовувати = для присвоєння, але не в кожному

контексті. Через незначні

відмінності у синтаксисі, рекомендується завжди використовувати

<- для присвоєння. Більше загалом ми віддаємо перевагу

синтаксису <- перед =, оскільки він дає

зрозуміти, в якому напрямку працює призначення (ліве призначення), і це

збільшує читабельність коду.

У RStudio ввівши Alt + - (натискайте

Alt одночасно з клавішею -) запише

<- за допомогою лише однієї комбінації швидких клавіш у

Windows. На Mac, те ж саме можна зробити, вводячи Option +

- (натискайте Option одночасно з клавішею

-).

Об’єктам можна дати будь-яку назву, наприклад x,

current_temperature або subject_id. Ви хочете,

щоб ваші назви об’єктів були явними й не надто довгими. Вони не можуть

починатися з числа (2x не є дійсним, але x2

є). R чутливий до регістру (наприклад, age відрізняється

від Age). Є деякі назви, які не можна використовувати,

оскільки вони є назвами фундаментальних об’єктів у R (наприклад,

if, else, for, див. тут

для повного списку). Загалом, навіть якщо це дозволено, краще не

використовувати їх (наприклад, c, T,

mean, data, df,

weights). Якщо ви сумніваєтесь, перевірте довідку, щоб

побачити, чи ім’я вже використовується. Також краще уникати крапок

(.) у назві об’єкта, як у my.dataset. Існує

багато об’єктів в R з крапками в назвах з історичних причин, але

оскільки точки мають особливе значення в R (для методів) та інших мовах

програмування, краще уникати їх. Рекомендований стиль написання

називається snake _case, що передбачає використання лише малих літер та

цифр та розділення кожного слова підкресленням (наприклад,

animal _weight, average _income). Також рекомендується використовувати

іменники для назв об’єктів, а дієслова для назв функцій. Важливо бути

послідовним у стилізації вашого коду (де ви розміщуєте пробіли, як ви

називаєте об’єкти тощо). Використання послідовного стилю кодування

робить ваш код зрозумілішим для читання для вас та ваших співробітників.

У R три популярні посібники зі стилю: Google, Jean

Fan’s та tidyverse. Tidyverse

дуже вичерпний і спочатку може здатися приголомшливим. Ви можете

встановити пакет lintr,

щоб автоматично перевіряти на наявність проблем у стилі вашого коду.

Об’єкти проти змінних

Іменування об’єктів у R якось пов’язане з

змінними у багатьох інших мовах програмування. У багатьох

мовах програмування змінна має три аспекти: ім’я, місце розташування

пам’яті та поточне значення, що зберігається в цьому місці.

R абстракції з модифікованих місць пам’яті. У

R ми маємо лише об’єкти, які можна назвати. Залежно від

контексту name (of a object)і variable можуть

мати різко різні значення. Однак у цьому уроці два слова

використовуються як синоніми. Для отримання додаткової інформації див.:

https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-lang.html#Objects

При присвоюванні значення назви, R не друкує нічого. Ви можете змусити R надрукувати значення за допомогою дужок або ввівши назву об’єкта:

R

area_hectares <- 1.0 # не виводить нічого

(area_hectares <- 1.0) # якщо взяти вираз у дужки — він надрукує значення `area_hectares`

OUTPUT

[1] 1R

area_hectares # друкує значення також, якщо просто ввести назву об’єкта

OUTPUT

[1] 1Тепер, коли R має area_hectares в пам’яті, ми можемо

робити з ним арифметичні операції. Наприклад, ми можемо захотіти

перетворити цю площу на гектари (площа в акрах дорівнює 2,47 р. більше

площі в гектарах):

R

2.47 * area_hectares

OUTPUT

[1] 2.47Ми також можемо змінити значення, присвоєне імені, призначивши йому нове:

R

area_hectares <- 2.5

2.47 * area_hectares

OUTPUT

[1] 6.175Це означає, що присвоєння значення одному імені не змінює значення

інших імен. Наприклад, назвемо площу ділянки в акрах

areaAcres:

R

area_acres <- 2.47 * area_hectares

потім змінити (перепризначити) area_hectares на 50.

R

area_hectares <- 50

Завдання

Як ви думаєте, яке поточне значення area_acres? 123.5

або 6.175?

The value of area_acres is still 6.175 because you have

not re-run the line area_acres <- 2.47 * area_hectares

since changing the value of area_hectares.

Comments

All programming languages allow the programmer to include comments in their code. Including comments to your code has many advantages: it helps you explain your reasoning and it forces you to be tidy. A commented code is also a great tool not only to your collaborators, but to your future self. Comments are the key to a reproducible analysis.

To do this in R we use the # character. Anything to the

right of the # sign and up to the end of the line is

treated as a comment and is ignored by R. You can start lines with

comments or include them after any code on the line.

R

area_hectares <- 1.0 # land area in hectares

area_acres <- area_hectares * 2.47 # convert to acres

area_acres # print land area in acres.

OUTPUT

[1] 2.47RStudio makes it easy to comment or uncomment a paragraph: after selecting the lines you want to comment, press at the same time on your keyboard Ctrl + Shift + C. If you only want to comment out one line, you can put the cursor at any location of that line (i.e. no need to select the whole line), then press Ctrl + Shift + C.

Exercise

Create two variables r_length and r_width

and assign them values. It should be noted that, because

length is a built-in R function, R Studio might add “()”

after you type length and if you leave the parentheses you

will get unexpected results. This is why you might see other programmers

abbreviate common words. Create a third variable r_area and

give it a value based on the current values of r_length and

r_width. Show that changing the values of either

r_length and r_width does not affect the value

of r_area.

R

r_length <- 2.5

r_width <- 3.2

r_area <- r_length * r_width

r_area

OUTPUT

[1] 8R

# change the values of r_length and r_width

r_length <- 7.0

r_width <- 6.5

# the value of r_area isn't changed

r_area

OUTPUT

[1] 8Functions and their arguments

Functions are “canned scripts” that automate more complicated sets of

commands including operations assignments, etc. Many functions are

predefined, or can be made available by importing R packages

(more on that later). A function usually gets one or more inputs called

arguments. Functions often (but not always) return a

value. A typical example would be the function

sqrt(). The input (the argument) must be a number, and the

return value (in fact, the output) is the square root of that number.

Executing a function (‘running it’) is called calling the

function. An example of a function call is:

R

b <- sqrt(a)

Here, the value of a is given to the sqrt()

function, the sqrt() function calculates the square root,

and returns the value which is then assigned to the name b.

This function is very simple, because it takes just one argument.

The return ‘value’ of a function need not be numerical (like that of

sqrt()), and it also does not need to be a single item: it

can be a set of things, or even a dataset. We’ll see that when we read

data files into R.

Arguments can be anything, not only numbers or filenames, but also other objects. Exactly what each argument means differs per function, and must be looked up in the documentation (see below). Some functions take arguments which may either be specified by the user, or, if left out, take on a default value: these are called options. Options are typically used to alter the way the function operates, such as whether it ignores ‘bad values’, or what symbol to use in a plot. However, if you want something specific, you can specify a value of your choice which will be used instead of the default.

Let’s try a function that can take multiple arguments:

round().

R

round(3.14159)

OUTPUT

[1] 3Here, we’ve called round() with just one argument,

3.14159, and it has returned the value 3.

That’s because the default is to round to the nearest whole number. If

we want more digits we can see how to do that by getting information

about the round function. We can use

args(round) or look at the help for this function using

?round.

R

args(round)

OUTPUT

function (x, digits = 0, ...)

NULLR

?round

We see that if we want a different number of digits, we can type

digits=2 or however many we want.

R

round(3.14159, digits = 2)

OUTPUT

[1] 3.14If you provide the arguments in the exact same order as they are defined you don’t have to name them:

R

round(3.14159, 2)

OUTPUT

[1] 3.14And if you do name the arguments, you can switch their order:

R

round(digits = 2, x = 3.14159)

OUTPUT

[1] 3.14It’s good practice to put the non-optional arguments (like the number you’re rounding) first in your function call, and to specify the names of all optional arguments. If you don’t, someone reading your code might have to look up the definition of a function with unfamiliar arguments to understand what you’re doing.

Exercise

Type in ?round at the console and then look at the

output in the Help pane. What other functions exist that are similar to

round? How do you use the digits parameter in

the round function?

Vectors and data types

A vector is the most common and basic data type in R, and is pretty

much the workhorse of R. A vector is composed by a series of values,

which can be either numbers or characters. We can assign a series of

values to a vector using the c() function. For example we

can create a vector of the number of household members for the

households we’ve interviewed and assign it to

hh_members:

R

hh_members <- c(3, 7, 10, 6)

hh_members

OUTPUT

[1] 3 7 10 6A vector can also contain characters. For example, we can have a

vector of the building material used to construct our interview

respondents’ walls (respondent_wall_type):

R

respondent_wall_type <- c("muddaub", "burntbricks", "sunbricks")

respondent_wall_type

OUTPUT

[1] "muddaub" "burntbricks" "sunbricks" The quotes around “muddaub”, etc. are essential here. Without the

quotes R will assume there are objects called muddaub,

burntbricks and sunbricks. As these names

don’t exist in R’s memory, there will be an error message.

There are many functions that allow you to inspect the content of a

vector. length() tells you how many elements are in a

particular vector:

R

length(hh_members)

OUTPUT

[1] 4R

length(respondent_wall_type)

OUTPUT

[1] 3An important feature of a vector, is that all of the elements are the

same type of data. The function typeof() indicates the type

of an object:

R

typeof(hh_members)

OUTPUT

[1] "double"R

typeof(respondent_wall_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"The function str() provides an overview of the structure

of an object and its elements. It is a useful function when working with

large and complex objects:

R

str(hh_members)

OUTPUT

num [1:4] 3 7 10 6R

str(respondent_wall_type)

OUTPUT

chr [1:3] "muddaub" "burntbricks" "sunbricks"You can use the c() function to add other elements to

your vector:

R

possessions <- c("bicycle", "radio", "television")

possessions <- c(possessions, "mobile_phone") # add to the end of the vector

possessions <- c("car", possessions) # add to the beginning of the vector

possessions

OUTPUT

[1] "car" "bicycle" "radio" "television" "mobile_phone"In the first line, we take the original vector

possessions, add the value "mobile_phone" to

the end of it, and save the result back into possessions.

Then we add the value "car" to the beginning, again saving

the result back into possessions.

We can do this over and over again to grow a vector, or assemble a dataset. As we program, this may be useful to add results that we are collecting or calculating.

An atomic vector is the simplest R data

type and is a linear vector of a single type. Above, we saw 2

of the 6 main atomic vector types that R uses:

"character" and "numeric" (or

"double"). These are the basic building blocks that all R

objects are built from. The other 4 atomic vector types

are:

-

"logical"forTRUEandFALSE(the boolean data type) -

"integer"for integer numbers (e.g.,2L, theLindicates to R that it’s an integer) -

"complex"to represent complex numbers with real and imaginary parts (e.g.,1 + 4i) and that’s all we’re going to say about them -

"raw"for bitstreams that we won’t discuss further

You can check the type of your vector using the typeof()

function and inputting your vector as the argument.

Vectors are one of the many data structures that R

uses. Other important ones are lists (list), matrices

(matrix), data frames (data.frame), factors

(factor) and arrays (array).

Exercise

We’ve seen that atomic vectors can be of type character, numeric (or double), integer, and logical. But what happens if we try to mix these types in a single vector?

R implicitly converts them to all be the same type.

Exercise (continued)

What will happen in each of these examples? (hint: use

class() to check the data type of your objects):

R

num_char <- c(1, 2, 3, "a")

num_logical <- c(1, 2, 3, TRUE)

char_logical <- c("a", "b", "c", TRUE)

tricky <- c(1, 2, 3, "4")

Why do you think it happens?

Vectors can be of only one data type. R tries to convert (coerce) the content of this vector to find a “common denominator” that doesn’t lose any information.

Exercise (continued)

How many values in combined_logical are

"TRUE" (as a character) in the following example:

R

num_logical <- c(1, 2, 3, TRUE)

char_logical <- c("a", "b", "c", TRUE)

combined_logical <- c(num_logical, char_logical)

Only one. There is no memory of past data types, and the coercion

happens the first time the vector is evaluated. Therefore, the

TRUE in num_logical gets converted into a

1 before it gets converted into "1" in

combined_logical.

Exercise (continued)

You’ve probably noticed that objects of different types get converted into a single, shared type within a vector. In R, we call converting objects from one class into another class coercion. These conversions happen according to a hierarchy, whereby some types get preferentially coerced into other types. Can you draw a diagram that represents the hierarchy of how these data types are coerced?

Subsetting vectors

Subsetting (sometimes referred to as extracting or indexing) involves accessing out one or more values based on their numeric placement or “index” within a vector. If we want to subset one or several values from a vector, we must provide one index or several indices in square brackets. For instance:

R

respondent_wall_type <- c("muddaub", "burntbricks", "sunbricks")

respondent_wall_type[2]

OUTPUT

[1] "burntbricks"R

respondent_wall_type[c(3, 2)]

OUTPUT

[1] "sunbricks" "burntbricks"We can also repeat the indices to create an object with more elements than the original one:

R

more_respondent_wall_type <- respondent_wall_type[c(1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 3)]

more_respondent_wall_type

OUTPUT

[1] "muddaub" "burntbricks" "sunbricks" "burntbricks" "muddaub"

[6] "sunbricks" R indices start at 1. Programming languages like Fortran, MATLAB, Julia, and R start counting at 1, because that’s what human beings typically do. Languages in the C family (including C++, Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0 because that’s simpler for computers to do.

Conditional subsetting

Another common way of subsetting is by using a logical vector.

TRUE will select the element with the same index, while

FALSE will not:

R

hh_members <- c(3, 7, 10, 6)

hh_members[c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE)]

OUTPUT

[1] 3 10 6Typically, these logical vectors are not typed by hand, but are the output of other functions or logical tests. For instance, if you wanted to select only the values above 5:

R

hh_members > 5 # will return logicals with TRUE for the indices that meet the condition

OUTPUT

[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUER

## so we can use this to select only the values above 5

hh_members[hh_members > 5]

OUTPUT

[1] 7 10 6You can combine multiple tests using & (both

conditions are true, AND) or | (at least one of the

conditions is true, OR):

R

hh_members[hh_members < 4 | hh_members > 7]

OUTPUT

[1] 3 10R

hh_members[hh_members >= 4 & hh_members <= 7]

OUTPUT

[1] 7 6Here, < stands for “less than”, > for

“greater than”, >= for “greater than or equal to”, and

== for “equal to”. The double equal sign == is

a test for numerical equality between the left and right hand sides, and

should not be confused with the single = sign, which

performs variable assignment (similar to <-).

A common task is to search for certain strings in a vector. One could

use the “or” operator | to test for equality to multiple

values, but this can quickly become tedious.

R

possessions <- c("car", "bicycle", "radio", "television", "mobile_phone")

possessions[possessions == "car" | possessions == "bicycle"] # returns both car and bicycle

OUTPUT

[1] "car" "bicycle"The function %in% allows you to test if any of the

elements of a search vector (on the left hand side) are found in the

target vector (on the right hand side):

R

possessions %in% c("car", "bicycle")

OUTPUT

[1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSENote that the output is the same length as the search vector on the

left hand side, because %in% checks whether each element of

the search vector is found somewhere in the target vector. Thus, you can

use %in% to select the elements in the search vector that

appear in your target vector:

R

possessions %in% c("car", "bicycle", "motorcycle", "truck", "boat", "bus")

OUTPUT

[1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSER

possessions[possessions %in% c("car", "bicycle", "motorcycle", "truck", "boat", "bus")]

OUTPUT

[1] "car" "bicycle"Missing data

As R was designed to analyze datasets, it includes the concept of

missing data (which is uncommon in other programming languages). Missing

data are represented in vectors as NA.

When doing operations on numbers, most functions will return

NA if the data you are working with include missing values.

This feature makes it harder to overlook the cases where you are dealing

with missing data. You can add the argument na.rm=TRUE to

calculate the result while ignoring the missing values.

R

rooms <- c(2, 1, 1, NA, 7)

mean(rooms)

OUTPUT

[1] NAR

max(rooms)

OUTPUT

[1] NAR

mean(rooms, na.rm = TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] 2.75R

max(rooms, na.rm = TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] 7If your data include missing values, you may want to become familiar

with the functions is.na(), na.omit(), and

complete.cases(). See below for examples.

R

## Extract those elements which are not missing values.

## The ! character is also called the NOT operator

rooms[!is.na(rooms)]

OUTPUT

[1] 2 1 1 7R

## Count the number of missing values.

## The output of is.na() is a logical vector (TRUE/FALSE equivalent to 1/0) so the sum() function here is effectively counting

sum(is.na(rooms))

OUTPUT

[1] 1R

## Returns the object with incomplete cases removed. The returned object is an atomic vector of type `"numeric"` (or `"double"`).

na.omit(rooms)

OUTPUT

[1] 2 1 1 7

attr(,"na.action")

[1] 4

attr(,"class")

[1] "omit"R

## Extract those elements which are complete cases. The returned object is an atomic vector of type `"numeric"` (or `"double"`).

rooms[complete.cases(rooms)]

OUTPUT

[1] 2 1 1 7Recall that you can use the typeof() function to find

the type of your atomic vector.

Exercise

- Using this vector of rooms, create a new vector with the NAs removed.

R

rooms <- c(1, 2, 1, 1, NA, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1, 1, 8, 3, 1, NA, 1)

Use the function

median()to calculate the median of theroomsvector.Use R to figure out how many households in the set use more than 2 rooms for sleeping.

R

rooms <- c(1, 2, 1, 1, NA, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1, 1, 8, 3, 1, NA, 1)

rooms_no_na <- rooms[!is.na(rooms)]

# or

rooms_no_na <- na.omit(rooms)

# 2.

median(rooms, na.rm = TRUE)

OUTPUT

[1] 1R

# 3.

rooms_above_2 <- rooms_no_na[rooms_no_na > 2]

length(rooms_above_2)

OUTPUT

[1] 4Now that we have learned how to write scripts, and the basics of R’s data structures, we are ready to start working with the SAFI dataset we have been using in the other lessons, and learn about data frames.

- Access individual values by location using

[]. - Access arbitrary sets of data using

[c(...)]. - Use logical operations and logical vectors to access subsets of data.

Content from Починаємо з даних

Last updated on 2026-01-17 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 80 minutes

Дві основні цілі цих уроків:

- Переконатися, що учасники впевнено працюють із датафреймом і можуть використовувати дужки для вибору рядків і стовпців.

- Виставити учнів як фактори. Їхня поведінка не завжди інтуїтивно зрозуміла, тому важливо, щоб учасників супроводжували під час роботи з ними вперше. The content of the lesson should be enough for learners to avoid common mistakes with them.

Overview

Questions

- Що таке датафрейм?

- Як я можу прочитати повний файл csv в R?

- Як я можу отримати основну зведену інформацію про мій набір даних?

- Як я можу змінити спосіб обробки R рядків у моєму наборі даних?

- Чому мені потрібно, щоб текстові рядки оброблялися інакше?

- Як у R представлені дати і як можна змінити їхній формат?

Objectives

- Описати що таке датафрейм.

- Завантажити зовнішні дані з файлу .csv в датафрейм.

- Підсумувати вміст датафрейму.

- Вибрати підмножину значень із датафреймів.

- Пояснити різницю між фактором і рядком.

- Перетворення між рядками та факторами.

- Упорядкувати та перейменувати фактори.

- Змінити спосіб обробки символьних рядків у датафреймі.

- Перевірити та змінити формат дат.

Що таке датафрейми?

Датафрейм - це стандартна структура даних для табличних даних у

R, яку ми використовуємо для обробки даних, статистичного

аналізу та візуалізації.

Датафрейм - це представлення даних у форматі таблиці, де стовпці є векторами, які мають однакову довжину. Датафрейми можна порівняти зі звичною електронною таблицею в програмах на кшталт Excel, але є одна важлива відмінність. Оскільки стовпці є векторами, кожен стовпець повинен містити один тип даних (наприклад, символи, цілі числа, фактори). Наприклад, на зображенні показано датафрейм, який складається з числового (numeric), текстового (character) та логічного (logical) векторів.

Датафрейм можна створювати вручну, але найчастіше вони генеруються

функціями read_csv()або read_table(); іншими

словами, при імпорті електронних таблиць з вашого жорсткого диска (або

Інтернету). Тепер ми продемонструємо, як імпортувати табличні дані за

допомогою read_csv().

Презентація даних SAFI

SAFI (Studying African Farmer-Led Irrigation) — це дослідження, яке вивчає методи ведення сільського господарства та іригації в Танзанії та Мозамбіку. Дані опитування були зібрані за допомогою інтерв’ю, проведених у період з листопада 2016 року до червня 2017 року. Для цього уроку ми будемо використовувати підмножину доступних даних. Для отримання інформації про повний навчальний набір даних, який використовується в інших уроках цього семінару, дивіться опис набору даних.

Ми будемо використовувати підмножину очищеної версії набору даних,

яку було створено шляхом очищення в OpenRefine

(data/SAFI_clean.csv). У цьому наборі даних відсутні

значення позначені як “NULL”, кожен рядок містить інформацію про одного

респондента інтерв’ю, а стовпці представляють:

| назва/стовпця | опис |

|---|---|

| key_id | Додано, щоб надати унікальний ідентифікатор для кожного спостереження. (Поле InstanceID також робить це, але воно не так зручно у використанні) |

| village | Назва села |

| interview_date | Дата співбесіди |

| no_membrs | Скільки членів у домогосподарстві? |

| years_liv | Скільки років ви живете в цьому селі чи сусідньому селі? |

| respondent_wall_type | Який тип стін має їхній будинок (зі списку) |

| rooms | Скільки кімнат в основному будинку використовується для сну? |

| memb_assoc | Ви член зрошувальної асоціації? |

| affect_conflicts | Ви постраждали від конфліктів з іншими іригаторами в цьому районі? |

| liv_count | Кількість тваринництва, що перебуває у власності. |

| items_owned | Які з перерахованих предметів належать домогосподарству? (список) |

| no_meals | Скільки страв люди у вашому домогосподарстві зазвичай їдять за день? |

| months_lack_food | Вкажіть, на які місяці, в останні 12 місяців ви стикалися з ситуацією, коли у вас не було достатньо їжі, щоб прогодувати домогосподарство? |

| instanceID | Унікальний ідентифікатор для подання даних форми |

Імпорт даних

Ви збираєтеся завантажити дані в пам’ять R за допомогою функції

read_csv() з пакета readr,

який є частиною tidyverse; дізнайтеся

більше про колекцію пакетів tidyverse тут.

readr встановлюється як частина

tidyverse встановлення. Коли ви

завантажуєте tidyverse

(library(tidyverse)), завантажуються основні пакети

(пакети, які використовуються в більшості аналізів даних), включаючи

readr.

Однак, перш ніж продовжити, це хороша можливість поговорити про

конфлікти. Деякі пакети, які ми завантажуємо, можуть в кінцевому

підсумку вводити імена функцій, які вже використовуються попередньо

завантаженими пакетами R. Наприклад, коли ми завантажимо пакет tidyverse

нижче, ми введемо дві суперечливі функції: filter()і

lag(). Це відбувається тому, що filter і

lag вже є функціями, які використовуються пакетом stats

(вже попередньо завантажений у R). Тепер, якщо ми, наприклад, викликаємо

функцію filter(), R використовуватиме

dplyr::filter() версії, а не stats::filter().

Це відбувається тому, що, якщо це конфлікт, за замовчуванням R

використовує функцію з останнього завантаженого пакета. Конфліктні

функції можуть викликати у вас певні проблеми в майбутньому, тому

важливо, щоб ми знали про них, щоб ми могли правильно обробляти їх, якщо

хочемо.

To do so, we just need the following functions from the conflicted package:

-

conflicted::conflict_scout(): Shows us any conflicted functions. -

conflict_prefer("function", "package_prefered"): Allows us to choose the default function we want from now on.

It is also important to know that we can, at any time, just call the

function directly from the package we want, such as

stats::filter().

Even with the use of an RStudio project, it can be difficult to learn

how to specify paths to file locations. Enter the here

package! The here package creates paths relative to the top-level

directory (your RStudio project). These relative paths work

regardless of where the associated source file lives inside

your project, like analysis projects with data and reports in different

subdirectories. This is an important contrast to using

setwd(), which depends on the way you order your files on

your computer.

Before we can use the read_csv() and here()

functions, we need to load the tidyverse and here packages.

Also, if you recall, the missing data is encoded as “NULL” in the

dataset. We’ll tell it to the function, so R will automatically convert

all the “NULL” entries in the dataset into NA.

R

library(tidyverse)

library(here)

interviews <- read_csv(

here("data", "SAFI_clean.csv"),

na = "NULL")

In the above code, we notice the here() function takes

folder and file names as inputs (e.g., "data",

"SAFI_clean.csv"), each enclosed in quotations

("") and separated by a comma. The here() will

accept as many names as are necessary to navigate to a particular file

(e.g.,

here("analysis", "data", "surveys", "clean", "SAFI_clean.csv)).

The here() function can accept the folder and file names

in an alternate format, using a slash (“/”) rather than commas to

separate the names. The two methods are equivalent, so that

here("data", "SAFI_clean.csv") and

here("data/SAFI_clean.csv") produce the same result. (The

slash is used on all operating systems; backslashes are not used.)

If you were to type in the code above, it is likely that the

read.csv() function would appear in the automatically

populated list of functions. This function is different from the

read_csv() function, as it is included in the “base”

packages that come pre-installed with R. Overall,

read.csv() behaves similar to read_csv(), with

a few notable differences. First, read.csv() coerces column

names with spaces and/or special characters to different names

(e.g. interview date becomes interview.date).

Second, read.csv() stores data as a

data.frame, where read_csv() stores data as a

different kind of data frame called a tibble. We prefer

tibbles because they have nice printing properties among other desirable

qualities. Read more about tibbles here.

The second statement in the code above creates a data frame but

doesn’t output any data because, as you might recall, assignments

(<-) don’t display anything. (Note, however, that

read_csv may show informational text about the data frame

that is created.) If we want to check that our data has been loaded, we

can see the contents of the data frame by typing its name:

interviews in the console.

R

interviews

## Try also

## view(interviews)

## head(interviews)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 131 × 14

key_ID village interview_date no_membrs years_liv respondent_wall_type

<dbl> <chr> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 1 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 4 muddaub

2 2 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 9 muddaub

3 3 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 10 15 burntbricks

4 4 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 6 burntbricks

5 5 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 40 burntbricks

6 6 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 3 muddaub

7 7 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 6 38 muddaub

8 8 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 12 70 burntbricks

9 9 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 8 6 burntbricks

10 10 Chirodzo 2016-12-16 00:00:00 12 23 burntbricks

# ℹ 121 more rows

# ℹ 8 more variables: rooms <dbl>, memb_assoc <chr>, affect_conflicts <chr>,

# liv_count <dbl>, items_owned <chr>, no_meals <dbl>, months_lack_food <chr>,

# instanceID <chr>Note

read_csv() assumes that fields are delimited by commas.

However, in several countries, the comma is used as a decimal separator

and the semicolon (;) is used as a field delimiter. If you want to read

in this type of files in R, you can use the read_csv2

function. It behaves exactly like read_csv but uses

different parameters for the decimal and the field separators. If you

are working with another format, they can be both specified by the user.

Check out the help for read_csv() by typing

?read_csv to learn more. There is also the

read_tsv() for tab-separated data files, and

read_delim() allows you to specify more details about the

structure of your file.

Note that read_csv() actually loads the data as a

tibble. A tibble is an extension of R data frames used by

the tidyverse. When the data is read using

read_csv(), it is stored in an object of class

tbl_df, tbl, and data.frame. You

can see the class of an object with

R

class(interviews)

OUTPUT

[1] "spec_tbl_df" "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame" As a tibble, the type of data included in each column is

listed in an abbreviated fashion below the column names. For instance,

here key_ID is a column of floating point numbers

(abbreviated <dbl> for the word ‘double’),

village is a column of characters

(<chr>) and the interview_date is a

column in the “date and time” format (<dttm>).

Inspecting data frames

When calling a tbl_df object (like

interviews here), there is already a lot of information

about our data frame being displayed such as the number of rows, the

number of columns, the names of the columns, and as we just saw the

class of data stored in each column. However, there are functions to

extract this information from data frames. Here is a non-exhaustive list

of some of these functions. Let’s try them out!

Size:

-

dim(interviews)- returns a vector with the number of rows as the first element, and the number of columns as the second element (the dimensions of the object) -

nrow(interviews)- повертає кількість рядків -

ncol(interviews)- повертає кількість стовпців

Content:

-

head(interviews)- shows the first 6 rows -

tail(interviews)- shows the last 6 rows

Names:

-

names(interviews)- returns the column names (synonym ofcolnames()fordata.frameobjects)

Summary:

-

str(interviews)- structure of the object and information about the class, length and content of each column -

summary(interviews)- summary statistics for each column -

glimpse(interviews)- returns the number of columns and rows of the tibble, the names and class of each column, and previews as many values will fit on the screen. Unlike the other inspecting functions listed above,glimpse()is not a “base R” function so you need to have thedplyrortibblepackages loaded to be able to execute it.

Note: most of these functions are “generic.” They can be used on other types of objects besides data frames or tibbles.

Subsetting data frames

Our interviews data frame has rows and columns (it has 2

dimensions). In practice, we may not need the entire data frame; for

instance, we may only be interested in a subset of the observations (the

rows) or a particular set of variables (the columns). If we want to

access some specific data from it, we need to specify the “coordinates”

(i.e., indices) we want from it. Row numbers come first, followed by

column numbers.

Tip

Subsetting a tibble with [ always results

in a tibble. However, note this is not true in general for

data frames, so be careful! Different ways of specifying these

coordinates can lead to results with different classes. This is covered

in the Software Carpentry lesson R for

Reproducible Scientific Analysis.

R

## first element in the first column of the tibble

interviews[1, 1]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 1

key_ID

<dbl>

1 1R

## first element in the 6th column of the tibble

interviews[1, 6]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 1

respondent_wall_type

<chr>

1 muddaub R

## first column of the tibble (as a vector)

interviews[[1]]

OUTPUT

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

[19] 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36

[37] 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54

[55] 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 127

[73] 133 152 153 155 178 177 180 181 182 186 187 195 196 197 198 201 202 72

[91] 73 76 83 85 89 101 103 102 78 80 104 105 106 109 110 113 118 125

[109] 119 115 108 116 117 144 143 150 159 160 165 166 167 174 175 189 191 192

[127] 126 193 194 199 200R

## first column of the tibble

interviews[1]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 131 × 1

key_ID

<dbl>

1 1

2 2

3 3

4 4

5 5

6 6

7 7

8 8

9 9

10 10

# ℹ 121 more rowsR

## first three elements in the 7th column of the tibble

interviews[1:3, 7]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 1

rooms

<dbl>

1 1

2 1

3 1R

## the 3rd row of the tibble

interviews[3, ]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 14

key_ID village interview_date no_membrs years_liv respondent_wall_type

<dbl> <chr> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 3 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 10 15 burntbricks

# ℹ 8 more variables: rooms <dbl>, memb_assoc <chr>, affect_conflicts <chr>,

# liv_count <dbl>, items_owned <chr>, no_meals <dbl>, months_lack_food <chr>,

# instanceID <chr>R

## equivalent to head_interviews <- head(interviews)

head_interviews <- interviews[1:6, ]

: is a special function that creates numeric vectors of

integers in increasing or decreasing order, test 1:10 and

10:1 for instance.

You can also exclude certain indices of a data frame using the

“-” sign:

R

interviews[, -1] # The whole tibble, except the first column

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 131 × 13

village interview_date no_membrs years_liv respondent_wall_type rooms

<chr> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

1 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 4 muddaub 1

2 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 9 muddaub 1

3 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 10 15 burntbricks 1

4 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 6 burntbricks 1

5 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 40 burntbricks 1

6 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 3 muddaub 1

7 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 6 38 muddaub 1

8 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 12 70 burntbricks 3

9 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 8 6 burntbricks 1

10 Chirodzo 2016-12-16 00:00:00 12 23 burntbricks 5

# ℹ 121 more rows

# ℹ 7 more variables: memb_assoc <chr>, affect_conflicts <chr>,

# liv_count <dbl>, items_owned <chr>, no_meals <dbl>, months_lack_food <chr>,

# instanceID <chr>R

interviews[-c(7:131), ] # Equivalent to head(interviews)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 14

key_ID village interview_date no_membrs years_liv respondent_wall_type

<dbl> <chr> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 1 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 4 muddaub

2 2 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 9 muddaub

3 3 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 10 15 burntbricks

4 4 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 6 burntbricks

5 5 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 40 burntbricks

6 6 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 3 muddaub

# ℹ 8 more variables: rooms <dbl>, memb_assoc <chr>, affect_conflicts <chr>,

# liv_count <dbl>, items_owned <chr>, no_meals <dbl>, months_lack_food <chr>,

# instanceID <chr>tibbles can be subset by calling indices (as shown

previously), but also by calling their column names directly:

R

interviews["village"] # Result is a tibble

interviews[, "village"] # Result is a tibble

interviews[["village"]] # Result is a vector

interviews$village # Result is a vector

In RStudio, you can use the autocompletion feature to get the full and correct names of the columns.

Завдання

- Create a tibble (

interviews_100) containing only the data in row 100 of theinterviewsdataset.

Now, continue using interviews for each of the following

activities:

- Notice how

nrow()gave you the number of rows in the tibble?

- Use that number to pull out just that last row in the tibble.

- Compare that with what you see as the last row using

tail()to make sure it’s meeting expectations. - Pull out that last row using

nrow()instead of the row number. - Create a new tibble (

interviews_last) from that last row.

Using the number of rows in the interviews dataset that you found in question 2, extract the row that is in the middle of the dataset. Store the content of this middle row in an object named

interviews_middle. (hint: This dataset has an odd number of rows, so finding the middle is a bit trickier than dividing n_rows by 2. Use the median( ) function and what you’ve learned about sequences in R to extract the middle row!Combine

nrow()with the-notation above to reproduce the behavior ofhead(interviews), keeping just the first through 6th rows of the interviews dataset.

R

## 1.

interviews_100 <- interviews[100, ]

## 2.

# Saving `n_rows` to improve readability and reduce duplication

n_rows <- nrow(interviews)

interviews_last <- interviews[n_rows, ]

## 3.

interviews_middle <- interviews[median(1:n_rows), ]

## 4.

interviews_head <- interviews[-(7:n_rows), ]

Фактори

R has a special data class, called factor, to deal with categorical data that you may encounter when creating plots or doing statistical analyses. Factors are very useful and actually contribute to making R particularly well suited to working with data. So we are going to spend a little time introducing them.

Factors represent categorical data. They are stored as integers

associated with labels and they can be ordered (ordinal) or unordered

(nominal). Factors create a structured relation between the different

levels (values) of a categorical variable, such as days of the week or

responses to a question in a survey. This can make it easier to see how

one element relates to the other elements in a column. While factors

look (and often behave) like character vectors, they are actually

treated as integer vectors by R. So you need to be very

careful when treating them as strings.

Once created, factors can only contain a pre-defined set of values, known as levels. By default, R always sorts levels in alphabetical order. For instance, if you have a factor with 2 levels:

R

respondent_floor_type <- factor(c("earth", "cement", "cement", "earth"))

R will assign 1 to the level "cement" and

2 to the level "earth" (because c

comes before e, even though the first element in this

vector is "earth"). You can see this by using the function

levels() and you can find the number of levels using

nlevels():

R

levels(respondent_floor_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "cement" "earth" R

nlevels(respondent_floor_type)

OUTPUT

[1] 2Sometimes, the order of the factors does not matter. Other times you

might want to specify the order because it is meaningful (e.g., “low”,

“medium”, “high”). It may improve your visualization, or it may be

required by a particular type of analysis. Here, one way to reorder our

levels in the respondent_floor_type vector would be:

R

respondent_floor_type # current order

OUTPUT

[1] earth cement cement earth

Levels: cement earthR

respondent_floor_type <- factor(respondent_floor_type,

levels = c("earth", "cement"))

respondent_floor_type # after re-ordering

OUTPUT

[1] earth cement cement earth

Levels: earth cementIn R’s memory, these factors are represented by integers (1, 2), but

are more informative than integers because factors are self describing:

"cement", "earth" is more descriptive than

1, and 2. Which one is “earth”? You wouldn’t

be able to tell just from the integer data. Factors, on the other hand,

have this information built in. It is particularly helpful when there

are many levels. It also makes renaming levels easier. Let’s say we made

a mistake and need to recode “cement” to “brick”. We can do this using

the fct_recode() function from the

forcats package (included in the

tidyverse) which provides some extra tools

to work with factors.

R

levels(respondent_floor_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "earth" "cement"R

respondent_floor_type <- fct_recode(respondent_floor_type, brick = "cement")

## as an alternative, we could change the "cement" level directly using the

## levels() function, but we have to remember that "cement" is the second level

# levels(respondent_floor_type)[2] <- "brick"

levels(respondent_floor_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "earth" "brick"R

respondent_floor_type

OUTPUT

[1] earth brick brick earth

Levels: earth brickSo far, your factor is unordered, like a nominal variable. R does not

know the difference between a nominal and an ordinal variable. You make

your factor an ordered factor by using the ordered=TRUE

option inside your factor function. Note how the reported levels changed

from the unordered factor above to the ordered version below. Ordered

levels use the less than sign < to denote level

ranking.

R

respondent_floor_type_ordered <- factor(respondent_floor_type,

ordered = TRUE)

respondent_floor_type_ordered # after setting as ordered factor

OUTPUT

[1] earth brick brick earth

Levels: earth < brickConverting factors

If you need to convert a factor to a character vector, you use

as.character(x).

R

as.character(respondent_floor_type)

OUTPUT

[1] "earth" "brick" "brick" "earth"Converting factors where the levels appear as numbers (such as

concentration levels, or years) to a numeric vector is a little

trickier. The as.numeric() function returns the index

values of the factor, not its levels, so it will result in an entirely

new (and unwanted in this case) set of numbers. One method to avoid this

is to convert factors to characters, and then to numbers. Another method

is to use the levels() function. Compare:

R

year_fct <- factor(c(1990, 1983, 1977, 1998, 1990))

as.numeric(year_fct) # Wrong! And there is no warning...

OUTPUT

[1] 3 2 1 4 3R

as.numeric(as.character(year_fct)) # Works...

OUTPUT

[1] 1990 1983 1977 1998 1990R

as.numeric(levels(year_fct))[year_fct] # The recommended way.

OUTPUT

[1] 1990 1983 1977 1998 1990Notice that in the recommended levels() approach, three

important steps occur:

- We obtain all the factor levels using

levels(year_fct) - We convert these levels to numeric values using

as.numeric(levels(year_fct)) - We then access these numeric values using the underlying integers of

the vector

year_fctinside the square brackets

Renaming factors

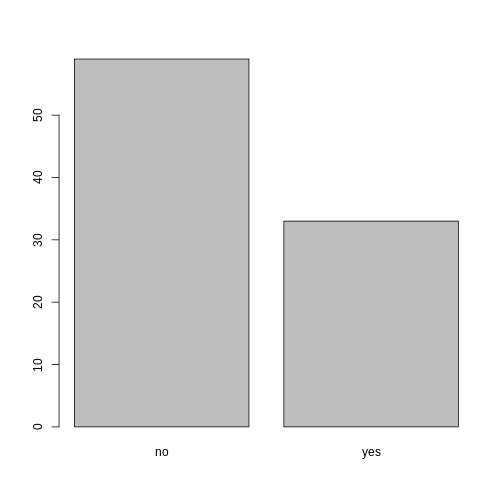

When your data is stored as a factor, you can use the

plot() function to get a quick glance at the number of

observations represented by each factor level. Let’s extract the

memb_assoc column from our data frame, convert it into a

factor, and use it to look at the number of interview respondents who

were or were not members of an irrigation association:

R

## create a vector from the data frame column "memb_assoc"

memb_assoc <- interviews$memb_assoc

## convert it into a factor

memb_assoc <- as.factor(memb_assoc)

## let's see what it looks like

memb_assoc

OUTPUT

[1] <NA> yes <NA> <NA> <NA> <NA> no yes no no <NA> yes no <NA> yes

[16] <NA> <NA> <NA> <NA> <NA> no <NA> <NA> no no no <NA> no yes <NA>

[31] <NA> yes no yes yes yes <NA> yes <NA> yes <NA> no no <NA> no

[46] no yes <NA> <NA> yes <NA> no yes no <NA> yes no no <NA> no

[61] yes <NA> <NA> <NA> no yes no no no no yes <NA> no yes <NA>

[76] <NA> yes no no yes no no yes no yes no no <NA> yes yes

[91] yes yes yes no no no no yes no no yes yes no <NA> no

[106] no <NA> no no <NA> no <NA> <NA> no no no no yes no no

[121] no no no no no no no no no yes <NA>

Levels: no yesR

## bar plot of the number of interview respondents who were

## members of irrigation association:

plot(memb_assoc)

Looking at the plot compared to the output of the vector, we can see that in addition to “no”s and “yes”s, there are some respondents for whom the information about whether they were part of an irrigation association hasn’t been recorded, and encoded as missing data. These respondents do not appear on the plot. Let’s encode them differently so they can be counted and visualized in our plot.

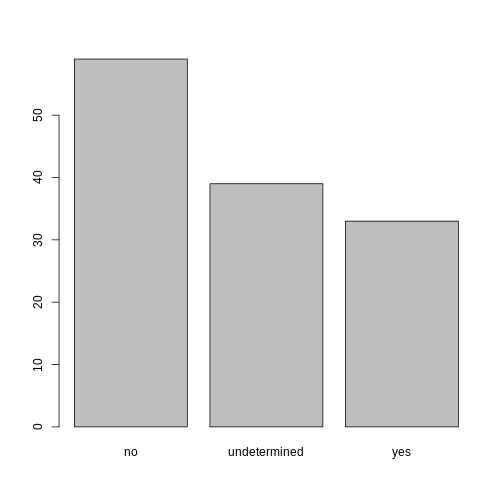

R

## Let's recreate the vector from the data frame column "memb_assoc"

memb_assoc <- interviews$memb_assoc

## replace the missing data with "undetermined"

memb_assoc[is.na(memb_assoc)] <- "undetermined"

## convert it into a factor

memb_assoc <- as.factor(memb_assoc)

## let's see what it looks like

memb_assoc

OUTPUT

[1] undetermined yes undetermined undetermined undetermined

[6] undetermined no yes no no

[11] undetermined yes no undetermined yes

[16] undetermined undetermined undetermined undetermined undetermined

[21] no undetermined undetermined no no

[26] no undetermined no yes undetermined

[31] undetermined yes no yes yes

[36] yes undetermined yes undetermined yes

[41] undetermined no no undetermined no

[46] no yes undetermined undetermined yes

[51] undetermined no yes no undetermined

[56] yes no no undetermined no

[61] yes undetermined undetermined undetermined no

[66] yes no no no no

[71] yes undetermined no yes undetermined

[76] undetermined yes no no yes

[81] no no yes no yes

[86] no no undetermined yes yes

[91] yes yes yes no no

[96] no no yes no no

[101] yes yes no undetermined no

[106] no undetermined no no undetermined

[111] no undetermined undetermined no no

[116] no no yes no no

[121] no no no no no

[126] no no no no yes

[131] undetermined

Levels: no undetermined yesR

## bar plot of the number of interview respondents who were

## members of irrigation association:

plot(memb_assoc)

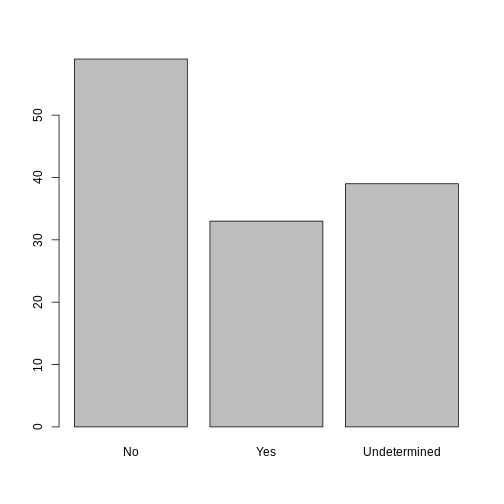

Завдання

Rename the levels of the factor to have the first letter in uppercase: “No”,“Undetermined”, and “Yes”.

Now that we have renamed the factor level to “Undetermined”, can you recreate the barplot such that “Undetermined” is last (after “Yes”)?

R

## Rename levels.

memb_assoc <- fct_recode(memb_assoc, No = "no",

Undetermined = "undetermined", Yes = "yes")

## Reorder levels. Note we need to use the new level names.

memb_assoc <- factor(memb_assoc, levels = c("No", "Yes", "Undetermined"))

plot(memb_assoc)

Formatting Dates

One of the most common issues that new (and experienced!) R users

have is converting date and time information into a variable that is

appropriate and usable during analyses. A best practice for dealing with

date data is to ensure that each component of your date is available as

a separate variable. In our dataset, we have a column

interview_date which contains information about the year,

month, and day that the interview was conducted. Let’s convert those

dates into three separate columns.

R

str(interviews)

We are going to use the package

lubridate, , which is included in the

tidyverse installation and should be

loaded by default. However, if we deal with older versions of tidyverse

(2022 and ealier), we can manually load it by typing

library(lubridate).

If necessary, start by loading the required package:

R

library(lubridate)

The lubridate function ymd() takes a vector representing

year, month, and day, and converts it to a Date vector.

Date is a class of data recognized by R as being a date and

can be manipulated as such. The argument that the function requires is

flexible, but, as a best practice, is a character vector formatted as

“YYYY-MM-DD”.

Let’s extract our interview_date column and inspect the

structure:

R

dates <- interviews$interview_date

str(dates)

OUTPUT

POSIXct[1:131], format: "2016-11-17" "2016-11-17" "2016-11-17" "2016-11-17" "2016-11-17" ...When we imported the data in R, read_csv() recognized

that this column contained date information. We can now use the

day(), month() and year()

functions to extract this information from the date, and create new

columns in our data frame to store it:

R

interviews$day <- day(dates)

interviews$month <- month(dates)

interviews$year <- year(dates)

interviews

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 131 × 17

key_ID village interview_date no_membrs years_liv respondent_wall_type

<dbl> <chr> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 1 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 4 muddaub

2 2 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 9 muddaub

3 3 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 10 15 burntbricks

4 4 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 6 burntbricks

5 5 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 7 40 burntbricks

6 6 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 3 3 muddaub

7 7 God 2016-11-17 00:00:00 6 38 muddaub

8 8 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 12 70 burntbricks

9 9 Chirodzo 2016-11-16 00:00:00 8 6 burntbricks

10 10 Chirodzo 2016-12-16 00:00:00 12 23 burntbricks

# ℹ 121 more rows

# ℹ 11 more variables: rooms <dbl>, memb_assoc <chr>, affect_conflicts <chr>,

# liv_count <dbl>, items_owned <chr>, no_meals <dbl>, months_lack_food <chr>,

# instanceID <chr>, day <int>, month <dbl>, year <dbl>Зверніть увагу на три нові стовпці в кінці нашого датафрейму.

In our example above, the interview_date column was read

in correctly as a Date variable but generally that is not

the case. Date columns are often read in as character

variables and one can use the as_date() function to convert

them to the appropriate Date/POSIXctformat.

Припустимо, у нас є вектор дат у символьному форматі:

R

char_dates <- c("7/31/2012", "8/9/2014", "4/30/2016")

str(char_dates)

OUTPUT

chr [1:3] "7/31/2012" "8/9/2014" "4/30/2016"We can convert this vector to dates as :

R

as_date(char_dates, format = "%m/%d/%Y")

OUTPUT

[1] "2012-07-31" "2014-08-09" "2016-04-30"Argument format tells the function the order to parse

the characters and identify the month, day and year. Формат вище - це

еквівалент мм/дд/рррр. Неправильний формат може призвести до помилок або

неправильних результатів.

For example, observe what happens when we use a lower case y instead of upper case Y for the year.

R

as_date(char_dates, format = "%m/%d/%y")

WARNING

Warning: 3 failed to parse.OUTPUT

[1] NA NA NAHere, the %y part of the format stands for a two-digit

year instead of a four-digit year, and this leads to parsing errors.

Or in the following example, observe what happens when the month and day elements of the format are switched.

R

as_date(char_dates, format = "%d/%m/%y")

WARNING

Warning: 3 failed to parse.OUTPUT

[1] NA NA NASince there is no month numbered 30 or 31, the first and third dates cannot be parsed.

We can also use functions ymd(), mdy() or

dmy() to convert character variables to date.

R

mdy(char_dates)

OUTPUT

[1] "2012-07-31" "2014-08-09" "2016-04-30"- Використовуйте read_csv для читання табличних даних у R.

- Використовуйте фактори для представлення категоріальних даних у R.

Content from Маніпулювання даними за допомогою пакету dplyr

Last updated on 2026-01-19 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

- Цей урок буде зрозумілішим, якщо використовувати графіки, які наочно демонструють роботу команд dplyr. Ви можете змінити цю презентацію Google Slides та використати для свого семінару.

- Для цього уроку переконайтеся, що учні впевнено користуються оператором pipe (%>%).