Content from Знайомство з терміналом

Останнє оновлення 2025-03-10 | Редагувати цю сторінку

Приблизний час: 5 хвилин

Огляд

Питання

- Що таке командний термінал і навіщо його використовувати?

Цілі

- Пояснити, як термінал пов’язаний з клавіатурою, екраном, операційною системою та програмами користувача.

- Пояснити, коли та чому інтерфейси командного рядка слід використовувати замість графічних інтерфейсів.

Попередні знання

Люди та комп’ютери зазвичай взаємодіють багатьма різними способами, наприклад за допомогою клавіатури та миші, сенсорного екрану або системи розпізнавання мови. Найбільш поширений спосіб взаємодії з персональними комп’ютерами називається графічний інтерфейс користувача (GUI - graphical user interface). За допомогою такого інтерфейсу ми надаємо комп’ютеру інструкції, обираючи дію у меню за допомогою миші.

Хоча візуальна допомога графічного інтерфейсу користувача робить інтуїтивним його вивчення, такий спосіб надсилання інструкцій до комп’ютера дуже погано масштабується. Уявіть наступну задачу: для бібліографічного пошуку вам необхідно скопіювати третій рядок з тисячі вхідних файлів з тисячі різних директорій та вставити усе це в один файл. Використовуючи графічний інтерфейс, ви б не тільки клацали мишею на свому робочому місці декілька годин, але й могли б потенційно також внести помилку в процесі виконання монотонної задачі. Саме тут ми й скористаємося перевагами терміналу Unix. Термінал Unix - це одночасно інтерфейс командного рядка (англ. “Command-Line Interface”, CLI) та скриптова мова програмування, яка дозволяє виконувати подібні повторювані задачі автоматично та швидко. За допомогою відповідних команд термінал може повторювати задачі із певними змінами або без них стільки разів, скільки ми бажаємо. З використанням терміналу приклад задачі з бібліографічним пошуком може бути вирішений за секунди.

Термінал

Термінал - це програма, де користувач може вводити команди. За допомогою терміналу можна запускати складні програми, такі як програмне забезпечення для моделювання клімату, або прості команди, які створюють пустий каталог, командами, які займають лише один рядок. Найбільш популярним терміналом є Bash (the Bourne Again SHell, який отримав таку назву, тому що був розроблений на основі терміналу, написаного Стівеном Борном). Bash є терміналом за замовчуванням у більшості сучасних реалізацій Unix та у більшості пакетів, які надають Unix-подібні інструменти для Windows. Зауважте, що ‘Git Bash’ — це частина програмного забезпечення, яка дозволяє користувачам Windows використовувати інтерфейс, подібний до Bash, при взаємодії з Git.

Щоб користуватися терміналом, потрібно докласти певних зусиль і витратити час на його вивчення. У той час як графічний інтерфейс надає вам можливість вибору, команди терміналу не надаються автоматично, тому вам доведеться вивчити кілька команд, як нову лексику у мові, яку ви вивчаєте. Однак, на відміну від розмовної мови, невелика кількість “слів” (тобто команд) принесе вам неймовірну користь, і сьогодні ми розглянемо кілька найважливіших з них.

Граматика терміналу дозволяє комбінувати наявні інструменти у потужні конвеєри та автоматично обробляти великі обсяги даних. Послідовності команд можуть бути записані у скрипт, покращуючи відтворюваність послідовностей дій.

Крім того, командний рядок часто є найпростішим способом взаємодії з віддаленими машинами та суперкомп’ютерами. Ознайомлення з терміналом є майже необхідним для запуску різноманітних спеціалізованих інструментів і ресурсів, у тому числі надпродуктивних обчислювальних систем. Оскільки кластери та хмарні обчислювальні системи стають все більш популярними для обробки наукових даних, вміння взаємодіяти з терміналом стає необхідною навичкою. Ми можемо розвивати навички роботи з командним рядком, описані тут, для вирішення широкого спектра наукових питань і обчислювальних проблем.

Отже, почнемо.

Коли термінал тільки відкрито, вам пропонується запит (англ. prompt), яке вказує на те, що термінал очікує на введення команд.

Термінал зазвичай використовує символ $ як запрошення,

але може використовувати й інші символи. У прикладах до цього уроку ми

використовуватимемо запрошення $. Найважливіше: під час

введення команд запрошення вводити не треба. Треба вводити

тільки команди, що йдуть за ним. Це правило діє як на цих уроках, так і

на уроках з інших джерел. Також зауважте, що після введення команди, вам

потрібно натиснути клавішу Enter для її виконання.

За запрошенням йде текстовий курсор - символ, який позначає позицію, де ви будете вводити текст. Курсор зазвичай блимає або є суцільним блоком, але він також може бути підкресленням або вертикальною рискою. Ви могли його бачити, наприклад, в текстових редакторах.

Зверніть увагу, що ваше запрошення може виглядати дещо інакше. Зокрема, більшість популярних середовищ оболонки за замовчуванням вказують ваше ім’я користувача та ім’я хоста перед ‘$’. Таке запрошення може виглядати, наприклад, так:

Запрошення може містити навіть ще більше інформації. Не хвилюйтеся,

якщо ваше запрошення - це не просто коротке $. Цей урок не

залежить від цієї додаткової інформації, та вона також не повинна вам

заважати. Єдиним важливим елементом, на якому слід зосередитися, є сам

символ $, і ми побачимо пізніше, чому.

Отже, спробуймо нашу першу команду, ls (походить від

англійського слова “listing”). Ця команда покаже зміст поточного

каталогу:

ВИХІД

Desktop Downloads Movies Pictures

Documents Library Music PublicКоманду не знайдено

Конвеєр Неллі: Типова Проблема

Неллі Немо (Nelle Nemo), морський біолог, щойно повернулась із

шестимісячного дослідження Північного

тихоокеанського кругообігу (North Pacific Gyre), де вона збирала

зразки драглистих морських організмів у Великій

тихоокеанській сміттєвій плямі. Вона має 1520 зразків, які вона

пропускає через аналізатор, щоб виміряти відносну кількість 300 білків.

Їй потрібно запустити ці 1520 файлів через уявну програму

goostats.sh, яку вона успадкувала. Окрім цього величезного

завдання, вона має написати результати до кінця місяця, щоб її робота

могла з’явитися у спеціальному випуску Aquatic Goo Letters.

Якщо Неллі вирішить запустити goostats.sh вручну за

допомогою графічного інтерфейсу, їй доведеться вибирати та відкривати

файли 1520 разів. Якщо обробка одного файлу програмою

goostats.sh триватиме 30 секунд, загальний процес

вимагатиме більше ніж 12 годин уваги Неллі. За допомогою терміналу,

Неллі може замість цього доручити своєму комп’ютеру цю рутинну роботу в

той час, коли вона фокусує свою увагу на написанні статті.

У наступних кількох уроках будуть розглянуті шляхи, яким чином Неллі

може цього досягти. Зокрема, на уроках пояснюється, як вона може

використовувати термінал для запуску програми goostats.sh,

використовуючи цикли для автоматизації повторюваних кроків введення імен

файлів, щоб її комп’ютер міг працювати, поки вона пише свою наукову

роботу.

Як бонус, після того, як вона створить конвеєр, вона зможе використовувати його повторно, коли вона збере більше даних.

Для того, щоб досягти своєї мети, Неллі необхідно знати, як:

- перейти до файла/каталогу

- створити файл/каталог

- перевірити довжину файлу

- з’єднати команди разом

- отримати набір файлів

- по черзі виконати дії над кожним файлом з набору

- запустити скрипт, що містить розроблений нею конвеєр

- Термінал - це програма, основним призначенням якої є читання команд і запуск інших програм.

- У цьому уроці використовується Bash. Це термінал за замовчуванням у багатьох реалізаціях Unix.

- Програми можна запускати у Bash шляхом введення команд у вікні командного рядка.

- Основними перевагами терміналу є високе співвідношення кількості дій до кількості натискань клавіш, підтримка автоматизації повторюваних завдань, а також можливість доступу до віддалених машин.

- Дуже важлива навичка при використанні оболонки - це вміння доречно використовувати текстові команди.

Content from Навігація по файловій системі

Останнє оновлення 2025-08-07 | Редагувати цю сторінку

Приблизний час: 40 хвилин

Огляд

Питання

- Як я можу пересуватися по файловій системі на моєму комп’ютері?

- Як я можу переглянути файли та каталоги на своєму комп’ютері?

- Як я можу вказати, де знаходиться файл або каталог на моєму комп’ютері?

Цілі

- Пояснити подібності та відмінності між файлом і каталогом.

- Перетворити абсолютний шлях у відносний і навпаки.

- Створити абсолютні та відносні шляхи, які ідентифікують певні файли та каталоги.

- Використати опції та аргументи для зміни поведінки команд у терміналі.

- Продемонструвати використання табуляції для автоматичного доповнення та пояснити його переваги.

Ознайомлення та навігація з файловою системою у терміналі (про яку йдеться у розділі Навігація файлами та каталогами) можуть бути складними. Ви можете відкрити термінал та графічний провідник файлів поруч, щоб учні могли бачити вміст і структуру файлів, коли вони використовують термінал для навігації системою.

Частина операційної системи, яка відповідає за роботу з файлами та каталогами, називається файловою системою. Вона організує наші дані у файли, які зберігають інформацію, та каталоги (також відомі як ‘теки’), які містять файли або інші підкаталоги.

Для створення, перевірки, перейменування та видалення файлів і каталогів зазвичай використовується декілька команд. Щоб розглянути їх, перейдемо до нашого відкритого вікна терміналу.

По-перше, дізнаймося, де ми знаходимося, запустивши команду

pwd (англ. ‘print working directory’ - надрукувати робочий

каталог). Каталоги подібні до місцезнаходження - у будь-який

момент, коли ми використовуємо термінал, ми знаходимося в одному місці,

яке називається поточним робочим каталогом. Команди

здебільшого читають та записують файли в поточний робочий каталог, тобто

“сюди”. Тому дуже важливо розуміти де ви знаходитесь перед виконанням

команди. Команда pwd покаже вам, де ви знаходитесь:

ВИХІД

/Users/nelleУ наведеному прикладі комп’ютер відповів /Users/nelle,

що є домашнім каталогом Неллі:

Варіації домашнього каталогу

Розташування домашнього каталогу виглядає по-різному в різних

операційних системах. В Linux воно може виглядати як

/home/nelle, а у Windows воно буде схоже на

C:\Documents and Settings\nelle чи

C:\Users\nelle. (Зауважте, що воно може виглядати дещо

інакше для різних версій Windows.) У наведених нижче прикладах ми

використовували результати у тому вигляді, у якому вони виглядають у

macOS. Хоча вихідні дані Linux і Windows можуть дещо відрізнятися,

загалом вони мають бути схожими.

Ми також припустимо, що ваша команда pwd повертає вашу

домашню директорію користувача. Якщо команда pwd повертає

щось інше, вам доведеться перейти у ваш домашній каталог за допомогою

команди cd, інакше деякі команди в цьому уроці не будуть

працювати належним чином. Дивіться Перегляд інших каталогів для

додаткової інформації про команду cd.

Для того, щоб зрозуміти, що таке ‘домашній каталог’, розглянемо як організована файлова система в цілому. Для цього прикладу ми проілюструємо файлову систему на комп’ютері морського біолога Неллі. Після цього прикладу ви вивчатимете команди для дослідження власної файлової системи, яка буде побудована подібним чином, але не буде абсолютно ідентичною.

На комп’ютері Неллі файлова система виглядає так:

Файлова система виглядає як перевернуте дерево. Найвищим каталогом є

кореневий каталог, який містить усе інше. Ми

посилаємося на нього за допомогою символу скісної риски /

(зауважте, що він є першим символом у рядку

/Users/nelle).

Усередині цього каталогу є кілька інших каталогів: bin

(в якому зберігаються певні вбудовані програми), data (для

різноманітних файлів даних), Users (де знаходяться особисті

директорії користувачів), tmp (для файлів тимчасового

зберігання) та інші.

Ми знаємо, що наш поточний робочий каталог /Users/nelle

зберігається всередині каталогу /Users, тому що

/Users є першою частиною його імені. Відповідно, нам

відомо, що каталог /Users зберігається всередині кореневої

директорії /, бо його ім’я розпочинається з символу

/.

Символи скісної риски

Зверніть увагу, що символ / має два значення. Коли він

з’являється на початку назви файлу чи каталогу, це посилання на кореневу

директорію. Коли він використовується всередині шляху, це лише

роздільник.

На комп’ютері Неллі, у каталозі /Users є підкаталог для

кожного користувача з обліковим записом, наприклад: для її колег

imhotep та larry.

Файли користувача imhotep зберігаються в каталозі

/Users/imhotep, користувача larry - в

/Users/larry, і Неллі - в /Users/nelle.

Оскільки саме Неллі є користувачем у наших прикладах, тому ми отримуємо

/Users/nelle як наш домашній каталог. Зазвичай, коли ви

відкриваєте нове вікно терміналу, ви опиняєтесь у своєму домашньому

каталозі.

Тепер розглянемо команду, яка дозволить нам бачити вміст нашої

власної файлової системи. Ми можемо побачити, що знаходиться у нашому

домашньому каталозі, запустивши ls:

ВИХІД

Applications Documents Library Music Public

Desktop Downloads Movies Pictures(Знову ж таки, ваші результати можуть дещо відрізнятися залежно від вашої операційної системи та того, як ви налаштували свою файлову систему.)

ls друкує назви файлів і каталогів у поточному каталозі.

Ми можемо зробити його вивід більш зрозумілим за допомогою

опції -F, яка вказує ls

класифікувати вивід, додаючи маркер до імен файлів і каталогів, щоб

вказати, що вони собою являють:

- символ

/наприкінці імені вказує на те, що це каталог - символ

@вказує на посилання - символ

*вказує на виконуваний файл

Залежно від налаштувань терміналу за замовчуванням, він також може використовувати кольори для позначення файлів та каталогів, щоб краще їх розрізняти.

ВИХІД

Applications/ Documents/ Library/ Music/ Public/

Desktop/ Downloads/ Movies/ Pictures/В наведеному прикладі ми бачимо, що наш домашній каталог містить лише підкаталоги. Будь-які імена у вихідних даних, які не мають символу класифікації, є файлами, розташованими в поточному робочому каталозі.

Як очистити термінал

Якщо екран стає занадто захаращеним, ви можете очистити термінал за

допомогою команди clear. Ви все ще можете отримати доступ

до попередніх команд за допомогою клавіш ↑ та ↓

для переміщення по рядках, або за допомогою прокрутки у вашому

терміналі.

Отримання допомоги

У ls є багато інших опцій. Існує два поширених способи

дізнатися, як використовувати команду і які параметри вона приймає —

залежно від вашого середовища, ви можете виявити, що працює лише

один із цих способів:

- Ми можемо передати команді опцію

--help(доступну в Linux і Git Bash), наприклад:

- Ми можемо переглянути інструкцію до використання команди за

допомогою

man(доступної на Linux і macOS), наприклад:

Далі ми роздивимось обидва способи.

Довідка для вбудованих команд

Деякі команди вбудовано в оболонку Bash, а не існують як окремі

програми у файловій системі. Одним із прикладів є команда

cd (зміна каталогу). Якщо після команди man cd

ви отримуєте повідомлення на кшталт No manual entry for cd,

спробуйте натомість help cd. За допомогою команди

help ви можете отримати інформацію про використання вбудованих

команд Bash.

Опція `–help’

Більшість команд bash і програм, написаних людьми для запуску з bash,

підтримують опцію --help, яка виводить додаткову інформацію

про те, як користуватися відповідною командою або програмою.

ВИХІД

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if neither -cftuvSUX nor --sort is specified.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options, too.

-a, --all do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all do not list implied . and ..

--author with -l, print the author of each file

-b, --escape print C-style escapes for nongraphic characters

--block-size=SIZE scale sizes by SIZE before printing them; e.g.,

'--block-size=M' prints sizes in units of

1,048,576 bytes; see SIZE format below

-B, --ignore-backups do not list implied entries ending with ~

-c with -lt: sort by, and show, ctime (time of last

modification of file status information);

with -l: show ctime and sort by name;

otherwise: sort by ctime, newest first

-C list entries by columns

--color[=WHEN] colorize the output; WHEN can be 'always' (default

if omitted), 'auto', or 'never'; more info below

-d, --directory list directories themselves, not their contents

-D, --dired generate output designed for Emacs' dired mode

-f do not sort, enable -aU, disable -ls --color

-F, --classify append indicator (one of */=>@|) to entries

... ... ...Коли використовувати короткі або довгі опції

Коли існують як короткі, так і довгі опції:

- Використовуйте коротку під час введення команд безпосередньо в термінал, щоб мінімізувати натискання клавіш і швидше виконувати завдання.

- Використовуйте довгу опцію у скриптах для наочності. Вона буде надрукована лише один раз, але прочитана багато разів.

Команда man

Інший спосіб дізнатися про ls - ввести

Ця команда виведе у вашому терміналі сторінку з описом команди

ls та її опцій.

Для навігації сторінками man ви можете використовувати

↑ і ↓ для переміщення по рядках, або спробувати

b і Spacebar для переходу вгору і вниз на цілу

сторінку. Для пошуку символу або слова на сторінках man,

використовуйте клавішу / та слідом введіть символ або слово,

яке ви шукаєте. Іноді пошук може призвести до кількох результатів. У

такому випадку ви можете переміщатися між результатами за допомогою

клавіш N (для переходу вперед) та

Shift+N (для переходу назад).

Щоб вийти зі сторінок man, натисніть

q.

Сторінки з інструкціями в Інтернеті

Звісно, є й третій спосіб отримати доступ до довідки для команд:

пошук в інтернеті за допомогою веббраузера. Якщо ви скористаєтеся

пошуком в Інтернеті, додання до запиту фрази unix man page

дозволить отримати більш доречні результати.

GNU надає посилання на свої посібники, зокрема на основні утиліти GNU, які охоплюють багато команд, представлених у цьому уроці.

Вивчення інших опцій ls

Ви також можете використовувати декілька опцій одночасно. Що робить

команда ls при використанні з опцією -l? А

якщо ви використовуєте -l та -h одночасно?

Деякі з результатів виконання команди стосуються властивостей, які ми не розглядаємо у цьому семінарі (наприклад, права доступу до файлів та їх власники), але решта все одно буде корисною.

Опція -l змушує ls використовувати довгий

(англ. long) формат виводу, показуючи не лише назви

файлів/директорій, але й додаткову інформацію, таку як розмір файлу і

час його останньої модифікації. Якщо ви використовуєте як

-h, так і -l, це зробить виведення розміру

файлу у більш зрозумілому людині вигляді (“human

readable”), тобто покаже щось на кшталт 5.3K замість

5369.

Виведення у зворотному хронологічному порядку

За замовчуванням ls виводить вміст каталогу в

алфавітному порядку за іменами елементів. Команда ls -t

перелічує елементи за часом останньої зміни, а не за алфавітом. Команда

ls -r виводить вміст каталогу у зворотному порядку. Який

файл буде показано останнім при комбінації опцій -t і

-r? Підказка: Вам потрібно скористатися опцією

-l, щоб переглянути дати останніх змін.

При використанні -rt останній змінений файл є останнім у

списку. Це може бути дуже корисним для пошуку ваших останніх редагувань

або перевірки чи було створено новий вихідний файл.

Перегляд інших каталогів

Ми можемо використовувати ls не лише у поточному

робочому каталозі, але й для виведення вмісту іншого каталогу.

Подивимося на наш каталог Desktop (робочий стіл), виконавши

ls -F Desktop, тобто, команду ls з

опцією -F і аргументом

Desktop. Аргумент Desktop повідомляє

ls, що ми хочемо отримати список чогось іншого, ніж наш

поточний робочий каталог:

ВИХІД

shell-lesson-data/Зауважте, що якщо у вашому поточному робочому каталозі не існує

каталогу з назвою Desktop, ця команда поверне помилку.

Зазвичай, підкаталог Desktop існує у вашому домашньому

каталозі, який ми вважаємо поточним робочим каталогом вашого терміналу

bash.

На виході ви маєте отримати список усіх файлів і підкаталогів у

вашому каталозі Desktop, включно з каталогом

shell-lesson-data, який ви завантажили за посиланням під

час налаштувань для цього уроку. (На більшості

систем вміст каталогу Desktop в терміналі можна побачити на

екрані у вигляді піктограм, якщо згорнути або закрити усі вікна у

графічному інтерфейсі користувача. Подивіться, чи це ваш випадок.)

Ієрархічна організація речей таким чином допомагає нам відстежувати нашу роботу. Хоча у нашому домашньому каталозі можна зберігати сотні файлів, так само як і сотні паперових документів на робочому столі, набагато легше знаходити речі, коли вони організовані у підкаталоги з розумними назвами.

Тепер, коли ми знаємо, що каталог shell-lesson-data

знаходиться у каталозі Desktop, ми можемо зробити дві речі.

По-перше, ми можемо переглянути його вміст, використовуючи ту ж

стратегію, що і раніше, передавши ім’я каталогу в ls:

ВИХІД

exercise-data/ north-pacific-gyre/По-друге, ми можемо змінити наше місцезнаходження на інший каталог, щоб ми більше не знаходилися в нашому домашньому каталозі.

Командою для зміни каталогів є cd, після якої йде назва

каталогу, до якого ви хочете перейти. Це оновить поточний робочий

каталог. cd означає ‘змінити каталог’ (англ. ‘change

directory’), що трохи вводить в оману. Команда не змінює сам каталог;

вона змінює поточний робочий каталог у терміналі. Іншими словами, вона

змінює налаштування терміналу щодо того, в якому каталозі ми

знаходимося. Команда cd подібна до подвійного клацання по

каталогу в графічному інтерфейсі, щоб потрапити до нього.

Припустимо, нам треба перейти до каталогу exercise-data,

який ми бачили вище. Ми можемо скористатися наступною серією команд, щоб

дістатися туди:

Ці команди перемістять нас з домашнього каталогу до Desktop, потім до

shell-lesson-data, а потім до exercise-data.

Ви помітите, що команда cd нічого не виводить. Це

нормально. Багато команд терміналу нічого не виводять на екран після

успішного виконання. Але якщо ми виконаємо pwd після неї,

то побачимо, що зараз ми знаходимося у

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-data.

Тепер, якщо ми виконаємо команду ls -F без аргументів,

вона виведе вміст

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-data, тому

що саме там ми зараз знаходимося:

ВИХІД

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-dataВИХІД

alkanes/ animal-counts/ creatures/ numbers.txt writing/Тепер ми знаємо, як рухатися вниз по дереву каталогів (тобто, як перейти до підкаталогу), але як рухатися вгору (тобто, як вийти з каталогу і перейти до його батьківського каталогу)? Ми можемо спробувати наступне:

ПОМИЛКА

-bash: cd: shell-lesson-data: No such file or directoryАле ми отримуємо помилку! Чому?

За допомогою поки що знайомих нам методів, cd може

бачити лише підкаталоги у вашому поточному каталозі. Існують різні

способи перегляду батьківських каталогів; ми почнемо з

найпростішого.

У терміналі є скорочення для переходу на один рівень каталогу вгору. Це працює наступним чином:

.. - це спеціальне ім’я каталогу, що означає “каталог,

що містить поточний”, або більш стисло, батько

поточного каталогу. Звичайно, якщо ми запустимо pwd після

виконання cd .., ми знову у

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-data:

ВИХІД

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-dataСпеціальний каталог .. зазвичай не з’являється, коли ми

запускаємо ls. Якщо ми хочемо побачити його, ми можемо

додати опцію -a до ls -F:

ВИХІД

./ ../ exercise-data/ north-pacific-gyre/-a означає ‘показати все’ (англ. show all) (включно з

прихованими файлами); ця опція змушує ls показувати нам

імена файлів і каталогів, які починаються з ., наприклад,

.. (яке, якщо ми знаходимося у /Users/nelle,

вказує на каталог /Users). Як ви можете бачити, команда

також показує ще один спеціальний каталог, який називається

., що означає ‘поточний робочий каталог’. Може здатися, що

це дещо надлишково - мати для нього ім’я, але незабаром ми побачимо, як

воно може бути використано.

Зауважте, що у більшості інструментів командного рядка можна

комбінувати декілька параметрів за допомогою одного - і без

пробілів між параметрами: ls -F -a є еквівалентним до

ls -Fa.

Інші приховані файли

Крім прихованих каталогів .. та ., ви також

можете побачити файл з назвою .bash_profile. Цей файл

зазвичай містить конфігурацію терміналу. Ви також можете зустріти інші

файли й каталоги, які починаються з символу .. Зазвичай це

конфігураційні файли та каталоги, які використовуються різними

програмами на вашому комп’ютері для налаштування. Префікс .

використовується для того, щоб ці конфігураційні файли не захаращували

термінал, коли використовується стандартна команда ls.

Ці три команди є основними командами для навігації по файловій

системі на вашому комп’ютері: pwd, ls і

cd. Розгляньмо деякі варіації цих команд. Що станеться якщо

ви введете команду cd саму по собі, не зазначаючи

каталог?

Як перевірити, що сталося? Команда pwd дає нам

відповідь!

ВИХІД

/Users/nelleВиявляється, cd без аргументу поверне вас до домашнього

каталогу, що дуже зручно, якщо ви загубилися у власній файловій

системі.

Спробуємо повернутися до каталогу exercise-data.

Минулого разу ми використовували три команди, але насправді ми можемо

поєднати перелік каталогів для переходу до каталогу

exercise-data за один крок:

Переконайтеся, що ми перемістилися в потрібне місце, виконавши

pwd і ls -F.

Щоб перейти на один рівень вище від каталогу даних, ми можемо

використати cd ... Але існує інший спосіб переміщення до

будь-якого каталогу, незалежно від вашого поточного розташування.

Дотепер, ми використовували відносні шляхи для вказування назви каталогів або навіть шляхів до каталогів (як описано вище). Він повідомляє таким командам, як ls або cd, знайти каталог на основі нашої поточної позиції у файловій системі, а не з кореня файлової системи.

Однак ми також можемо використовувати абсолютні

шляхи, які вказують повне розташування каталогу, починаючи від

кореневого каталогу, який позначається символом скісної риски (/).

Символ / на початку абсолютного шляху вказує комп’ютеру

слідувати шляхом від кореня файлової системи, тому шлях інтерпретується

однаково, незалежно від нашого поточного каталогу.

Це дає змогу перейти до каталогу shell-lesson-data з

будь-якого місця у файловій системі (у тому числі з каталогу

exercise-data). Щоб знайти абсолютний шлях ми можемо

скористатися pwd, а потім витягти потрібний нам фрагмент,

щоб перейти до shell-lesson-data.

ВИХІД

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-dataВиконайте pwd і ls -F, щоб переконатися, що

ми знаходимося в потрібному каталозі.

Ще два скорочення

Термінал інтерпретує символ тильди (~) на початку шляху

як “домашній каталог поточного користувача”. Наприклад, якщо домашнім

каталогом користувача Неллі є каталог /Users/nelle, то

~/data еквівалентно /Users/nelle/data. Це

працює лише у випадку, якщо це перший символ у шляху:

here/there/~/elsewhere не

єhere/there/Users/nelle/elsewhere.

Іншим скороченням є символ - (тире). cd

інтерпретує - як попередній каталог, у якому я

був, що є швидше, ніж запам’ятовувати, а потім набирати повний

шлях. Це дуже ефективний спосіб переміщення між двома

каталогами - тобто, якщо ви виконаєте cd - двічі, це

повертає вас до початкового каталогу.

Різниця між cd .. і cd - полягає в тому, що

перший переміщується на один рівень вище в ієрархії каталогів,

а другий повертає вас назад.

Спробуйте! Спочатку перейдіть до

~/Desktop/shell-lesson-data (ви вже маєте бути там).

Потім cd у каталог

exercise-data/creatures

Тепер, якщо ви виконаєте

ви побачите, що повернулися до

~/Desktop/shell-lesson-data. Запустіть cd - ще

раз і ви повернетесь до

~/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/creatures

Абсолютні та відносні шляхи

Якщо Неллі зараз знаходиться в /Users/nelle/data, то яка

з наведених нижче команд дозволить їй повернутися до її домашнього

каталогу /Users/nelle?

cd .cd /cd /home/nellecd ../..cd ~cd homecd ~/data/..cdcd ..

Ні: скорочення

.означає поточний каталог.Ні: скорочення

/означає кореневий каталог.Ні: домашнім каталогом Неллі є

/Users/nelle.Ні: ця команда переходить на два рівні вгору, тобто до

/Users.Так: символ

~позначає домашній каталог користувача, у цьому випадку/Users/nelle.Ні: ця команда виконає перехід до каталогу

homeу поточному каталозі, якщо він існує.Так: надмірно складна, але правильна.

Так: скорочення для повернення до домашнього каталогу користувача.

Так: підіймається на один рівень вище в структурі каталогів.

Завдання відносного шляху

Використовуючи наведену нижче схему файлової системи, якщо

pwd показує /Users/thing, що покаже команда

ls -F ../backup?

../backup: No such file or directory (не існує такого файлу або каталогу)2012-12-01 2013-01-08 2013-01-272012-12-01/ 2013-01-08/ 2013-01-27/original/ pnas_final/ pnas_sub/

Ні: у каталозі

/Usersіснує підкаталогbackup.Ні: це вміст каталогу

Users/thing/backup, але за допомогою..ми просили піднятися на один рівень вище.Ні: див. попереднє пояснення.

Так:

../backup/вказує на/Users/backup/.

Розуміння команди ls

Звертаючись до діаграми файлової системи нижче, якщо pwd

повертає /Users/backup, а параметр -r у

команді ls змінює порядок виведення результатів, яка (які)

команда (команди) призведе до наступного результату:

ВИХІД

pnas_sub/ pnas_final/ original/ls pwdls -r -Fls -r -F /Users/backup

Ні:

pwdне є назвою каталогу.Так: команда

lsбез аргументу перелічує файли й каталоги у поточному каталозі.Так: чітко використовує абсолютний шлях.

Загальний синтаксис команд терміналу

Ми вже познайомилися з командами, опціями та аргументами, але, можливо, буде корисно формалізувати деяку термінологію.

Розглянемо команду нижче як приклад і розберемо її на складові частини:

ls - це команда, з

опцією -F та аргументом

/. Ми вже зустрічалися з опціями, які починаються з одного

тире (-), відомі як короткі варіанти, або

двох тире (--), відомі як довгі варіанти.

[Опції] змінюють поведінку команди, а [аргументи] вказують команді, над

чим вона має працювати (наприклад, над файлами й каталогами). Іноді

опції та аргументи називають параметрами. Команда може

сприймати кілька параметрів і аргументів, але вона не завжди вимагає

їх.

Опції також іноді називають перемикачами або прапорцями, особливо якщо вони не приймають аргументів. У цьому уроці ми будемо дотримуватися терміну опція.

Кожна частина відокремлюється пробілами. Якщо ви пропустите пробіл

між ls і -F, термінал шукатиме команду з

назвою ls-F, якої не існує. Також, параметри чутливі до

регістру. Наприклад, ls -s покаже розміри файлів та

каталогів поряд з їхніми назвами., а ls -S відсортує файли

та каталоги за розміром, як показано нижче:

ВИХІД

total 28

4 animal-counts 4 creatures 12 numbers.txt 4 alkanes 4 writingЗверніть увагу, що розміри, які повертає команда ls -s,

подано у блоках. Оскільки вони визначаються по-різному для

різних операційних систем, ви можете отримати не такі значення, як у

прикладі.

ВИХІД

animal-counts creatures alkanes writing numbers.txtЗібравши все це разом, команда ls -F / вище дасть нам

список файлів і каталогів у кореневому каталозі /. Нижче

наведено приклад результату, який ви можете отримати від цієї

команди:

ВИХІД

Applications/ System/

Library/ Users/

Network/ Volumes/Конвеєр Неллі: Організація файлів

Знаючи так багато про файли та каталоги, Неллі готова впорядкувати файли, які створить машина для аналізу білків.

Вона створює каталог під назвою north-pacific-gyre (щоб

нагадати собі, звідки взялися дані), який міститиме файли даних з

аналітичної машини та її скрипти для обробки даних.

Кожному фізичному зразку присвоюється унікальний десятисимвольний

ідентифікатор, наприклад ‘NENE01729A’, згідно з затвердженими в

лабораторії правилами. Оскільки цей ідентифікатор вона використовує у

своєму журналі для документування таких деталей, як місцезнаходження,

часу і глибини, то вона додає його до імен своїх файлів даних. Оскільки

результат роботи аналізатора є звичайним текстом, вона назве свої файли

NENE01729A.txt, NENE01812A.txt і так далі. Усі

1520 файлів буде збережено в одному каталозі.

Тепер у її поточному каталозі shell-lesson-data, Неллі

може побачити, які файли вона має за допомогою цієї команди:

Ця команда вимагає багато друку, але Неллі може мінімізувати зусилля, використовуючи табуляцію, що дозволяє терміналу автоматично завершувати команди та імена файлів. Якщо вона набере:

а потім натисне клавішу Tab (клавішу табуляції на її клавіатурі), то термінал автоматично доповнить назву каталогу для неї:

Повторне натискання клавіші Tab нічого не дасть, оскільки існує декілька варіантів; якщо натиснути Tab двічі, буде показано список усіх відповідних файлів.

Якщо Неллі потім натисне щеG і знову Tab, оболонка додасть ‘goo’, оскільки всі файли, що починаються з ‘g’, мають спільні перші три символи ‘goo’.

Щоб побачити всі ці файли, вона може натиснути клавішу Tab ще двічі.

Ця функція відома як автодоповнення табуляцією, і ми зустрінемо її у багатьох інших інструментах протягом цього уроку.

- Файлова система відповідає за керування інформацією на диску.

- Інформація зберігається у файлах, які зберігаються в каталогах (теках).

- Каталоги також можуть зберігати інші підкаталоги, які таким чином створюють дерево каталогів.

- Команда

pwdвиводить поточний робочий каталог користувача. - Команда

ls [path]виводить список з певного файлу або каталогу; командаlsсама по собі виводить список поточного робочого каталогу. - Команда

cd [path]змінює поточний робочий каталог. - Більшість команд приймають параметри, які починаються з одного

символу

-. - Назви каталогів в шляху розділяються символами

/в Unix, але\в Windows. - Символ

/сам по собі зазначає кореневий каталог усієї файлової системи. - Абсолютний шлях вказує на розташування відносно кореня файлової системи.

- Відносний шлях вказує на розташування, починаючи з поточного каталогу.

- Символ

.сам по собі означає ‘поточний каталог’;..означає ‘батьківський каталог’ (той, що знаходиться над поточним каталогом).

Content from Робота з файлами та каталогами

Останнє оновлення 2025-08-28 | Редагувати цю сторінку

Приблизний час: 50 хвилин

Огляд

Питання

- Як я можу створювати, копіювати та видаляти файли і каталоги?

- Як я можу редагувати файли?

Цілі

- Створити ієрархію каталогів, яка відповідає заданій схемі.

- Створити файли в цій ієрархії за допомогою редактора або шляхом копіювання та перейменування файлів, що вже існують.

- Видалити, скопіювати та перемістити вказані файли та/або каталоги.

Створення каталогів

Тепер ми знаємо, як досліджувати файли та каталоги, але як їх створювати?

У цьому уроці ми дізнаємося про створення та переміщення файлів і

каталогів на прикладі каталогу exercise-data/writing.

Крок перший: подивимось, де ми знаходимося і що вже маємо

Ми все ще маємо бути у каталозі shell-lesson-data на

Робочому столі (англ. Desktop), що ми можемо перевірити за

допомогою:

ВИХІД

/Users/nelle/Desktop/shell-lesson-dataДалі ми перейдемо до каталогу exercise-data/writing і

подивимося, що у ньому міститься:

ВИХІД

haiku.txt LittleWomen.txtСтворення каталогу

Створимо новий каталог з назвою thesis за допомогою

команди mkdir thesis (яка не має виводу):

Як ви можете здогадатися з її назви, команда mkdir

означає ‘створити каталог’ (англ. ‘make directory’). Оскільки

thesis є відносним шляхом (тобто не має початкової косої

риски, як /what/ever/thesis), новий каталог буде створено у

поточному робочому каталозі:

ВИХІД

haiku.txt LittleWomen.txt thesis/Оскільки ми щойно створили каталог thesis, у ньому ще

нічого немає:

Зауважте, що команда mkdir не тільки створює окремі

каталоги по одному за раз. Параметр -p дозволяє команді

mkdir створювати каталог із вкладеними підкаталогами за

одну операцію:

Параметр -R з командою ls покаже усі

вкладені підкаталоги у каталозі. Скористаймось ls -FR для

рекурсивного зображення нової ієрархії каталогів, яку ми щойно створили

у каталозі project:

ВИХІД

../project/:

data/ results/

../project/data:

../project/results:Два способи зробити одне й те саме

Використання терміналу для створення каталогу нічим не відрізняється

від використання файлового провідника. Якщо ви зараз відкриєте поточний

каталог за допомогою графічного провідника файлів вашої операційної

системи, там також з’явиться каталог thesis. Хоча термінал

і файловий провідник - це два різні способи взаємодії з файлами, самі

файли й каталоги одні й ті ж самі.

Доречні імена для файлів і каталогів

Використання надто складних імен для файлів і каталогів може ускладнити роботу в командному рядку. Ось кілька корисних порад щодо вибору ефективних імен.

- Не використовуйте пробіли.

Пробіли можуть зробити назву більш змістовною, але оскільки вони

використовуються для відокремлення аргументів у командному рядку, краще

уникати їх у назвах файлів і каталогів. Ви можете використовувати

- або _ (наприклад,

north-pacific-gyre/ замість

north pacific gyre/). Щоб перевірити це, спробуйте набрати

mkdir north pacific gyre і подивіться, який каталог (або

каталоги!) буде створено, перевірив це за допомогою

ls -F.

- Не починайте назву з

-(тире).

Команди розглядають назви, що починаються з -, як

опції.

- Використовуйте літери, цифри,

.(крапку),-(тире) і_(підкреслення).

Багато інших символів мають особливе значення у командному рядку. Деякі з них ми розглянемо у цьому уроці. Існують спеціальні символи, які можуть спричинити неправильну роботу команди й навіть призвести до втрати даних.

Якщо вам потрібно звернутися до назв файлів або каталогів, які

містять пробіли чи інші спеціальні символи, вам слід узяти назву в

одинарні лапки

('').

Початківці іноді не знають, як вийти з таких редакторів, як Vim, Emacs чи Nano. Закриття терміналу та відкриття нового вікна може бути незручним, оскільки учням доведеться знову переходити до потрібного каталогу. Для пом’якшення цієї проблеми ми радимо викладачам використовувати той самий текстовий редактор, що й учні під час семінарів (у більшості випадків Nano).

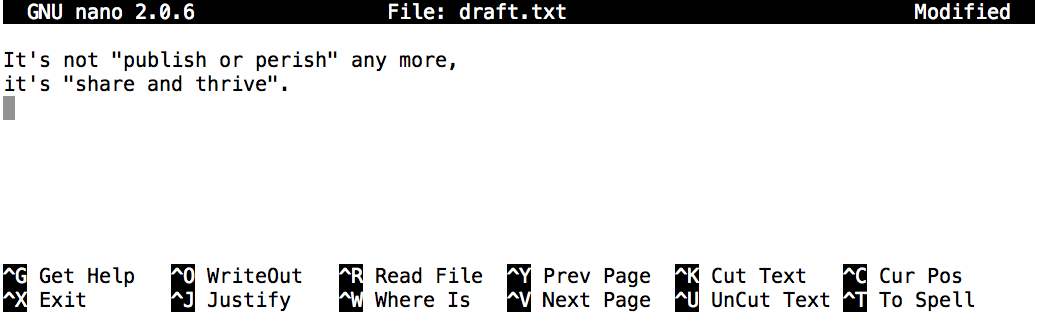

Створення текстового файлу

Перейдімо до каталогу thesis за допомогою

cd, а потім запустимо текстовий редактор Nano та створимо

файл з назвою draft.txt:

Який редактор використовувати?

Коли ми говоримо, що ‘nano - це текстовий редактор’, ми

дійсно маємо на увазі ‘текстовий’. У ньому неможливо переглядати або

редагувати таблиці, зображення чи будь-які інші зручні для сприйняття

людиною дані. Ми використовуємо його у прикладах, оскільки це один із

найпростіших текстових редакторів. Однак, через це він може виявитися

недостатньо потужним або гнучким для складніших завдань, які вам

потрібно буде виконати після завершення цього семінару. У системах Unix

(таких як Linux та macOS), багато програмістів використовують [Emacs]

(https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/) чи Vim (обидва вимагають більше часу на

вивчення), або графічний редактор, такий як Gedit чи VScode. У Windows, можливо, ви

захочете скористатися Notepad++. Операційна система

Windows також має вбудований редактор з назвою notepad,

який можна запустити з командного рядка так само, як і nano

для цього семінару.

Незалежно від того, яким редактором ви користуєтеся, вам потрібно знати, де він шукає і зберігає файли. Якщо ви запускаєте його з термінала, він (імовірно) використовуватиме ваш поточний робочий каталог як розташування за замовчуванням. Однак, якщо ви використовуєте меню “Пуск” вашого комп’ютера, файли за замовчуванням можуть зберігатися замість цього на робочому столі або в каталозі “Документи” (Documents). Ви можете змінити це, перейшовши до іншого каталогу під час першого виконання команди “Зберегти як…” (“Save As…”).

Наберемо кілька рядків тексту.

{alt=“Скриншот текстового

редактора nano в дії з текстом”У минулому це було - публікуй чи зникни,

а наразі стало - ділися та процвітай”}

{alt=“Скриншот текстового

редактора nano в дії з текстом”У минулому це було - публікуй чи зникни,

а наразі стало - ділися та процвітай”}

Як тільки ми будемо задоволені нашим текстом, нам треба використати

комбінацію Ctrl+O (утримуючи клавішу

Ctrl or Control, натисніть клавішу O),

щоб зберегти наші дані на диск. Потім нам буде запропоновано вказати

ім’я файлу, у якому зберігатиметься наш текст. Натисніть

Return, щоб прийняти запропоновану за замовчуванням назву

draft.txt.

Як тільки файл було збережено, скористаємось комбінацією клавіш Ctrl+X, щоб вийти з редактора і повернутися до термінала.

Клавіша Control, Ctrl або ^

Клавіші Control також називається клавішею ‘Ctrl’. Існує декілька способів, якими може бути описане використання клавіші Control. Наприклад, ви можете побачити вказівку натиснути клавішу Control і, утримуючи її натиснутою, потім натиснути клавішу X, описану будь-яким з наступних способів:

Control-XControl+XCtrl-XCtrl+X^XC-x

У nano, у нижній частині екрана ви побачите

^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. Це означає, що ви можете

скористатися Control-G для отримання довідки й

Control-O для збереження вашого файлу.

Після завершення роботи команда nano не залишає жодних

даних на екрані, але ls тепер показує, що ми створили файл

з назвою draft.txt:

ВИХІД

draft.txtСтворення файлів іншим способом

Ми побачили, як створювати текстові файли за допомогою редактора

nano. Тепер спробуйте виконати наступну команду:

Що зробила команда

touch? Якщо ви відкриєте поточний каталог у файловому провіднику, чи видно в ньому цей файл?Скористуйтеся

ls -lдля перегляду файлів. Який розмір має файлmy_file.txt?У яких випадках доцільно створювати файл саме таким чином?

Команда

touchстворює новий файл з назвоюmy_file.txtу вашому поточному каталозі. Щоб переконатися, що файл створено, скористайтеся командоюls. Файлmy_file.txtтакож можна переглянути у вашому графічному провіднику файлів.Коли ви перевіряєте файл за допомогою

ls -l, зверніть увагу, що розмірmy_file.txt— 0 байт. Це означає, що файл порожній. Якщо відкрити його в редакторі, ви не знайдете в ньому жодного вмісту.Іноді програми не генерують вихідні файли автоматично, а потребують, щоб порожні файли були створені заздалегідь. Потім під час виконання програма шукає наявний файл, щоб заповнити його своїми даними. За допомогою команди

touchможна ефективно створити порожній текстовий файл для подальшого використання такими програмами.

Що ховається в імені?

Ви, мабуть, помітили, що всі файли Неллі називаються ‘щось крапка

щось’, і у цій частині уроку ми завжди використовували розширення

.txt. Це лише умовність: ми можемо назвати файл

mythesis або майже як завгодно. Однак, більшість людей

здебільшого використовують назви, що складаються з двох частин для того,

щоб допомогти їм (і їхнім програмам) розрізняти різні типи файлів. Друга

частина такого імені називається розширенням файлу і вказує тип даних у

файлі: .txt вказує на простий текстовий файл,

.pdf вказує на PDF-документ, .cfg - це

конфігураційний файл з параметрами для тієї чи іншої програми,

.png - зображення у форматі PNG, і так далі.

Це лише умовність, хоча й важлива. Файли містять лише байти: це ми та наші програми будемо їх відповідно інтерпретувати — як текст, PDF-документи, конфігураційні файли, зображення тощо.

Якщо ви назвете зображення кита у форматі PNG як

whale.mp3, це не перетворить його якимось чарівним чином на

запис пісні кита, хоча це може змусити операційну систему

спробувати відкрити його за допомогою музичного плеєра. У цьому випадку,

якщо хтось двічі клацне на файлі whale.mp3 у файловому

провіднику, музичний програвач автоматично (і помилково) спробує

відкрити файл whale.mp3.

Переміщення файлів і каталогів

Повернемося до каталогу

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/writing:

У нашому каталозі thesis є файл draft.txt,

з не надто інформативною назвою, тому змінімо назву файлу за допомогою

команди mv, що є скороченням від ‘move’ (з англ. -

‘переміщати’):

Перший аргумент говорить mv, що ми “переміщаємо”, а

другий - куди саме. У цьому випадку ми переміщуємо

thesis/draft.txt до thesis/quotes.txt, що має

той самий ефект, що і перейменування файлу. Після цього ls

підтверджує, що thesis тепер містить один файл з назвою

quotes.txt:

ВИХІД

quotes.txtСлід бути обережним, вказуючи ім’я цільового файлу, оскільки

mv приховано перезапише будь-який наявний файл з такою

самою назвою, а це може призвести до втрати даних. За замовчуванням

mv не запитуватиме підтвердження перед перезаписом файлів.

Однак додатковий параметр mv -i (або

mv --interactive) змусить mv запросити таке

підтвердження.

Зверніть увагу, що mv також працює з каталогами.

Перемістимо quotes.txt до поточного робочого каталогу.

Знову скористаємося mv, але цього разу ми використаємо лише

назву каталогу як другий аргумент щоб повідомити mv, що ми

хочемо зберегти назву файлу, але перемістити файл у нове місце. (Ось

чому команда називається ‘перемістити’.) У цьому випадку ми

використовуємо спеціальну назву . поточного каталогу, про

яку ми згадували раніше.

Наслідком цього буде переміщення файлу з початкового каталогу до

поточного робочого каталогу. Тепер ls показує нам, що

каталог thesis` порожній:

ВИХІД

$Крім того, ми можемо переконатися, що файл quotes.txt

більше не присутній у каталозі thesis, спробувавши показати

інформацію про нього:

ПОМИЛКА

ls: cannot access 'thesis/quotes.txt': No such file or directoryКоманда ls, якщо вказати ім’я файлу або каталогу як

аргумент, виводить лише список запитуваних файлів або каталогів. Якщо

вказаного файлу не існує, термінал поверне помилку — як ми вже бачили

раніше. Таким чином ми можемо перевірити, що файл

quotes.txt тепер знаходиться у поточному каталозі:

ВИХІД

quotes.txtПереміщення файлів до нового каталогу

Після виконання наступних команд Джеймі зрозуміла, що помістила файли

sucrose.dat та maltose.dat не до того

каталогу. Файли потрібно було помістити у каталог raw.

BASH

$ ls -F

analyzed/ raw/

$ ls -F analyzed

fructose.dat glucose.dat maltose.dat sucrose.dat

$ cd analyzedЗаповніть пропуски, щоб перемістити ці файли до каталогу

raw/ (тобто туди, куди вона забула їх помістити)

Копіювання файлів і каталогів

Команда cp працює майже так само, як і mv,

але замість переміщення копіює файл. Ми можемо перевірити результат за

допомогою ls з двома шляхами у ролі параметрів, адже

ls та більшість команд Unix здатні приймати декілька

аргументів одночасно:

ВИХІД

quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txtМи також можемо скопіювати каталог і весь його вміст за допомогою рекурсивної опції

-r, наприклад, для створення резервної копії каталогу:

Ми можемо перевірити результат, переглянувши вміст каталогів

thesis та thesis_backup:

ВИХІД

thesis:

quotations.txt

thesis_backup:

quotations.txtВажливо додати опцію -r. Якщо ви хочете скопіювати

каталог і не вкажете цей параметр ви побачите повідомлення про те, що

каталог було пропущено, оскільки -r не вказано.

Перейменування файлів

Припустімо, що ви створили у поточному каталозі простий текстовий

файл, який містить список статистичних тестів, які вам знадобляться для

аналізу ваших даних, і назвали його statstics.txt

Після створення і збереження цього файлу ви зрозуміли, що неправильно написали назву файлу! Ви хочете виправити помилку. Яку з наведених нижче команд ви можете використати для цього?

cp statstics.txt statistics.txtmv statstics.txt statistics.txtmv statstics.txt .cp statstics.txt .

- Ні. Хоча це створить файл з правильною назвою, неправильно названий файл все одно існуватиме у каталозі, і його потрібно буде видалити.

- Так, це спрацює для перейменування файлу.

- Ні, крапка (.) вказує, куди перемістити файл, але не надає нового імені файлу; файли з однаковими іменами не можуть бути створені.

- Ні, крапка (.) вказує, куди скопіювати файл, але не надає нового імені файлу; файли з однаковими іменами не можуть бути створені.

Переміщення та копіювання

Що виводить остання команда ls у наведеній нижче

послідовності?

ВИХІД

/Users/jamie/dataВИХІД

proteins.datBASH

$ mkdir recombined

$ mv proteins.dat recombined/

$ cp recombined/proteins.dat ../proteins-saved.dat

$ lsproteins-saved.dat recombinedrecombinedproteins.dat recombinedproteins-saved.dat

Ми розпочинаємо роботу в каталозі /Users/jamie/data і

створюємо нову папку з назвою recombined. Другий рядок

переміщує (mv) файл proteins.dat до нового

каталогу (recombined). Третій рядок робить копію файлу,

який ми щойно перемістили. Складність полягає у тому, куди саме було

скопійовано цей файл. Нагадаємо, що .. означає “піднятися

на рівень вище”, тому скопійований файл тепер знаходиться у

/Users/jamie. Зверніть увагу, що ..

інтерпретується відносно поточного робочого каталогу, а

не відносно розташування файлу, який копіюється. Отже,

єдине, що буде показано за допомогою команди ls (у каталозі

/Users/jamie/data) - це каталог

recombined.

- Ні, див. пояснення вище. Каталог

proteins-saved.datрозташовано у каталозі/Users/jamie - Так

- Ні, див. пояснення вище. Файл

proteins.datзнаходиться в каталозі/Users/jamie/data/recombined - Ні, див. пояснення вище. Файл

proteins-saved.datзнаходиться в каталозі/Users/jamie

Видалення файлів і каталогів

Повертаючись до каталогу

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/writing, давайте почистимо

цей каталог, видаливши створений нами файл quotes.txt. Для

цього ми скористаємося командою Unix rm (скорочення від

англ. remove - видаляти):

Ми можемо перевірити видалення файлу за допомогою

ls:

ПОМИЛКА

ls: cannot access 'quotes.txt': No such file or directoryВидалення - це назавжди

В терміналі Unix немає кошика для відновлення видалених файлів (хоча у більшості графічних інтерфейсів Unix він є). Натомість коли ми видаляємо файли, вони від’єднуються від файлової системи, щоб їх місце на диску можна було використати повторно. Інструменти для пошуку та відновлення видалених файлів існують, але вони не гарантують успішного відновлення, оскільки комп’ютер може відразу перезаписати місце, яке займав файл.

Безпечне використання rm

Що відбувається, коли ми виконуємо

rm -i thesis_backup/quotations.txt? Навіщо нам може бути

потрібен цей захист при використанні rm?

ВИХІД

rm: remove regular file 'thesis_backup/quotations.txt'? yПараметр -i призведе до окремого запиту перед (кожним)

вилученням (використовуйте Y для підтвердження вилучення або

N, щоб зберегти файл). У командному терміналі Unix немає

кошика, тому видалені файли зникнуть назавжди. Використання опції

-i дає можливість перевірити, що ми видаляємо лише обрані

файли.

Якщо ми спробуємо видалити каталог thesis за допомогою

rm thesis, ми отримаємо повідомлення про помилку:

ПОМИЛКА

rm: cannot remove `thesis': Is a directoryЦе відбувається тому, що команда rm за замовчуванням

працює лише з файлами, а не з каталогами.

Команда rm може видалити каталог і весь його вміст, якщо

додати рекурсивний параметр -r, і це станеться без жодних

запитів на підтвердження:

Оскільки файли, видалені за допомогою терміналу не відновлюються,

команду rm -r слід застосовувати з великою обережністю (ви

можете додати інтерактивну опцію rm -r -i).

Операції з декількома файлами та каталогами

Час від часу нам знадобиться скопіювати або перемістити кілька файлів одночасно. Для цього треба надати список імен окремих файлів, або вказати шаблон імен за допомогою символів підстановки. Це символи, які можна використовувати для представлення невідомих символів або груп символів під час навігації по файловій системі Unix.

Копіювання кількох файлів водночас

Для цієї вправи ви можете випробувати команди у каталозі

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data.

Що робить команда cp у наведеному нижче прикладі, коли

їй надано декілька імен файлів і назву каталогу?

Що робить команда cp у наведеному нижче прикладі, коли

їй задано три або більше імен файлів?

ВИХІД

basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.datЯкщо надано декілька імен файлів та ім’я каталогу (каталог

призначення має бути останнім аргументом), команда cp

копіює файли до вказаного каталогу.

Якщо надано тільки три імені файлів, то cp видасть

помилку, подібну до наведеної нижче, бо останній аргумент повинен бути

ім’ям каталогу.

ПОМИЛКА

cp: target 'basilisk.dat' is not a directoryВикористання символів підстановки для роботи з кількома файлами одночасно

Символи підстановки

Символ * - це символ підстановки

(wildcard), який відповідає нулю або більшій кількості будь-яких

символів. Розглянемо каталог

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/proteins:

*.pdb відповідає ethane.pdb,

propane.pdb і кожному файлу, який закінчується на ‘.pdb’. З

іншого боку, p*.pdb підходить тільки для файлів

pentane.pdb і propane.pdb, оскільки початкова

літера ‘p’ лише збігається з назвами файлів, які починаються з літери

‘p’.

Символ ? також є символом підстановки, але він

відповідає рівно одному будь-якому символу. Отже,

?ethane.pdb буде відповідати methane.pdb, тоді

як *ethane.pdb відповідає як ethane.pdb, так і

methane.pdb.

Символи підстановки можна використовувати разом, комбінуючи їх у

шаблонах. Наприклад, ???ane.pdb відповідає трьом символам,

за якими слідує ane.pdb, що дає

cubane.pdb ethane.pdb octane.pdb.

Коли термінал бачить символ підстановки, він розгортає його для

створення списку відповідних імен файлів до запуску команди,

яку було введено. Як виняток, якщо вираз підстановки не відповідає

жодному файлу, Bash передасть вираз як аргумент до команди, якою вона є.

Наприклад, введення ls *.pdf у каталозі

proteins (який містить лише файли з іменами, що

закінчуються на .pdb) призведе до повідомлення про те, що

не існує файлу з назвою *.pdf. Втім, зазвичай команди на

кшталт wc і ls показують списки імен файлів,

які відповідають цим виразам, але не самим символам підстановки. Саме

термінал, а не інші програми, виконує розкриття символів

підстановки.

Отримання переліку імен файлів, що відповідають шаблону

При виконанні в каталозі alkanes, яка з команд

ls видасть наступний результат?

ethane.pdb methane.pdb

ls *t*ane.pdbls *t?ne.*ls *t??ne.pdbls ethane.*

Відповіддю є 3.

1. показує всі файли, назви яких починаюьться з нуля або

більше символів (*), за якими йде літера t,

потім нуль або більше символів (*) і далі

ane.pdb. Це дасть

ethane.pdb methane.pdb octane.pdb pentane.pdb.

2. показує всі файли, назви яких починаються з нуля або

більше символів (*), за якими йде літера t,

потім один будь-який символ (?), потім ne. і

далі нуль або більше символів (*). Це дасть нам

octane.pdb і pentane.pdb, але не збігається ні

з чим, що закінчується на thane.pdb.

3. виправляє проблеми варіанта 2, вимагаючи два символи

(??) між t і ne. Це і є

рішення.

4. показує лише файли, що починаються з

ethane..

Більше про символи підстановки

Саманта має каталог, який містить дані калібрування, набори даних та їх описи:

BASH

.

├── 2015-10-23-calibration.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset_overview.txt

├── 2015-10-26-calibration.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset_overview.txt

├── 2015-11-23-calibration.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset_overview.txt

├── backup

│ ├── calibration

│ └── datasets

└── send_to_bob

├── all_datasets_created_on_a_23rd

└── all_november_filesПеред тим, як вирушити на чергову польову подорож, вона хоче створити резервну копію даних і надіслати деякі набори своєму колезі Бобу. Саманта використовує наступні команди щоб виконати цю роботу:

BASH

$ cp *dataset* backup/datasets

$ cp ____calibration____ backup/calibration

$ cp 2015-____-____ send_to_bob/all_november_files/

$ cp ____ send_to_bob/all_datasets_created_on_a_23rd/Допоможіть Саманті, заповнивши пропуски.

Отримана структура каталогів повинна виглядати наступним чином:

BASH

.

├── 2015-10-23-calibration.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-10-23-dataset_overview.txt

├── 2015-10-26-calibration.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-10-26-dataset_overview.txt

├── 2015-11-23-calibration.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset2.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset_overview.txt

├── backup

│ ├── calibration

│ │ ├── 2015-10-23-calibration.txt

│ │ ├── 2015-10-26-calibration.txt

│ │ └── 2015-11-23-calibration.txt

│ └── datasets

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset1.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset2.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset_overview.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-26-dataset1.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-26-dataset2.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-26-dataset_overview.txt

│ ├── 2015-11-23-dataset1.txt

│ ├── 2015-11-23-dataset2.txt

│ └── 2015-11-23-dataset_overview.txt

└── send_to_bob

├── all_datasets_created_on_a_23rd

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset1.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset2.txt

│ ├── 2015-10-23-dataset_overview.txt

│ ├── 2015-11-23-dataset1.txt

│ ├── 2015-11-23-dataset2.txt

│ └── 2015-11-23-dataset_overview.txt

└── all_november_files

├── 2015-11-23-calibration.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset1.txt

├── 2015-11-23-dataset2.txt

└── 2015-11-23-dataset_overview.txtУпорядкування каталогів і файлів

Джеймі працює над проєктом і бачить, що її файли не дуже добре впорядковані:

ВИХІД

analyzed/ fructose.dat raw/ sucrose.datФайли fructose.dat та sucrose.dat містять

результати її аналізу. Яку (які) команду (команди), розглянуту

(розглянуті) у цьому уроці, їй потрібно виконати, щоб наведені нижче

команди вивели результати наведені нижче?

ВИХІД

analyzed/ raw/ВИХІД

fructose.dat sucrose.datВідтворення структури каталогів

Ви починаєте новий експеримент і бажаєте продублювати структуру каталогів з попереднього експерименту, щоб потім додати нові дані.

Припустимо, що попередній експеримент знаходиться у каталозі з назвою

2016-05-18, який містить каталог data, який

аналогічно містить каталоги raw і processed у

яких містяться файли даних. Мета полягає у копіюванні структури

2016-05-18 до каталогу 2016-05-20 таким чином,

щоб ваша фінальна структура виглядала наступним чином:

ВИХІД

2016-05-20/

└── data

├── processed

└── rawЯкий з наведених нижче наборів команд досягне цієї мети? Що зроблять інші команди?

Перші два набори команд досягають цієї мети. Перший набір використовує відносні шляхи для створення каталогу верхнього рівня перед створенням підкаталогів.

Третій набір команд призведе до помилки, оскільки поведінка

mkdir за замовчуванням не створює підкаталог в каталозі, що

не існує: спочатку мають бути створені каталоги проміжних рівнів.

Четвертий набір команд теж досягає цієї мети. Пам’ятайте, що опція

-p, після якої вказується шлях до одного або декількох

каталогів, змусить mkdir створити будь-які проміжні

підкаталоги за потреби.

Останній набір команд створить каталоги ‘raw’ і ‘processed’ на тому ж рівні, що і каталог ‘data’.

-

cp [old] [new]копіює файл. -

mkdir [path]створює новий каталог. -

mv [old] [new]переміщує (перейменовує) файл або каталог. -

rm [path]вилучає (видаляє) файл. -

*відповідає нулю або більшій кількості символів в імені файлу, тому*.txtвідповідає всім файлам, імена яких закінчуються на.txt. -

?відповідає будь-якому одному символу у назві файлу, тому?.txtвідповідаєa.txt, але неany.txt. - Використання клавіші Control можна описати різними способами,

зокрема

Ctrl-X,Control-Xта^X. - В терміналі немає кошика для сміття: як тільки щось видалено - його неможливо відновити.

- Більшість файлів мають назву на кшталт “щось.розширення”. Розширення не є обов’язковим і нічого не гарантує, але зазвичай використовується для позначення типу даних у файлі.

- Залежно від типу вашої роботи вам може знадобитися потужніший ніж Nano текстовий редактор.

Content from Канали та фільтри

Останнє оновлення 2025-09-04 | Редагувати цю сторінку

Приблизний час: 35 хвилин

Огляд

Питання

- Як я можу комбінувати команди, що вже існують, щоб робити нові речі?

- Як відобразити лише частину виведених даних?

Цілі

- Зрозуміти перевагу поєднання команд за допомогою каналів та фільтрів.

- Навчитись комбінувати послідовності команд для отримання нового результату

- Навчитись перенаправляти вивід команди до файлу.

- Зрозуміти, що зазвичай відбувається, якщо програмі або конвеєру не надається жодних вхідних даних для обробки.

Тепер, після ознайомлення з основними командами, ми можемо нарешті

розглянути найпотужнішу функцію терміналу: здатність комбінувати наявні

програми різними способами. Ми почнемо з каталогу

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/proteins, який містить

шість файлів, що описують деякі прості органічні молекули. Розширення

.pdb вказує на те, що ці файли мають формат Protein Data

Bank - простий текстовий формат, який визначає тип і положення кожного

атома в молекулі.

ВИХІД

cubane.pdb methane.pdb pentane.pdb

ethane.pdb octane.pdb propane.pdbЗапустимо наприклад цю команду:

ВИХІД

20 156 1158 cubane.pdbwc - команда для підрахунку слів (англ. ‘word count’):

вона рахує кількість рядків, слів і символів у файлах (повертаючи

значення в такому порядку зліва направо).

Якщо ми виконаємо команду wc *.pdb, то символ

* у *.pdb відповідає будь-якій кількості

символів (включаючи пустий рядок), тож термінал перетворить

*.pdb на перелік усіх файлів з розширенням

.pdb у поточному каталозі:

ВИХІД

20 156 1158 cubane.pdb

12 84 622 ethane.pdb

9 57 422 methane.pdb

30 246 1828 octane.pdb

21 165 1226 pentane.pdb

15 111 825 propane.pdb

107 819 6081 totalЗверніть увагу, що wc *.pdb в останньому рядку свого

виводу також показує загальну кількість усіх рядків у перелічених

файлах.

Якщо ми виконаємо wc -l замість просто wc,

то виводитиметься лише кількість рядків у файлах:

ВИХІД

20 cubane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

9 methane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

107 totalПараметри -m та -w з командою

wc дозволяють показувати тільки кількість символів або

тільки кількість слів у файлах.

Чому нічого не відбувається?

Що станеться, коли команді, яка має обробляти файл, не надати його назву? Наприклад, що буде, якщо ми наберемо:

але не будемо вводити *.pdb (або щось інше) після цієї

команди? Оскільки команда не отримала жодних назв файлів,

wc вважає, що треба обробляти введені дані з командного

рядка, тому вона просто очікує, поки ми надамо їй якісь дані

інтерактивно. Ззовні, однак, це виглядає так, ніби команда нічого не

робить.

Якщо ви припустилися такої помилки, ви можете вийти з цього стану, утримуючи клавішу control (Ctrl), та один раз натиснувши клавішу C: Ctrl+C. Потім відпустіть обидві клавіші.

Перехоплення виводу з команд

Який з цих файлів містить найменшу кількість рядків? Це легко визначити, коли файлів лише шість, але що робити, якщо їх 6000? Наш перший крок до пошуку рішення - це запуск наступної команди:

Символ ‘більше ніж’, тобто >, вказує терміналу

перенаправити вивід команди до файлу замість виведення

його на екран. Ця команда не виводить дані на екран, оскільки увесь

вивід wc записується до файлу lengths.txt.

Якщо файлу не існувало до виконання команди, його буде створено. Якщо

файл вже існує, він буде непомітно перезаписаний, що може призвести до

втрати даних. Таким чином, перенаправлення команд

вимагає обережності.

Команда ls lengths.txt підтверджує, що файл існує:

ВИХІД

lengths.txtТепер ми можемо вивести вміст файлу lengths.txt на екран

за допомогою команди cat lengths.txt. Назва команди

cat походить від слова ‘concatenate’, тобто об’єднувати, і

вона виводить вміст файлів один за одним. У цьому випадку є лише один

файл, тому cat просто виводить нам його вміст:

ВИХІД

20 cubane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

9 methane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

107 totalВиведення сторінки за сторінкою

У цьому уроці, для зручності та послідовності ми й надалі

використовуватимемо команду cat, але її недолік полягає в

тому, що вона завжди показує весь файл одразу. Більш корисною на

практиці є команда less (наприклад,

less lengths.txt). Вона виводить стільки вмісту файлу,

скільки вміщується в одному екрані, а потім робить паузу. Ви можете

перейти на один екран вперед, натиснувши пробіл, або на один екран

назад, натиснувши клавішу b. Щоб вийти з перегляду вмісту

файлу, натисніть q.

Фільтрування виводу

Далі ми скористаємося командою sort для сортування

вмісту файлу lengths.txt. Але спершу виконаємо вправу, щоб

трохи ознайомитися з командою sort:

Що робить sort -n?

Файл shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/numbers.txt містить

наступні рядки:

10

2

19

22

6Якщо ми виконаємо команду sort для цього файлу, то

отримаємо наступне:

ВИХІД

10

19

2

22

6Якщо ми виконаємо команду sort -n для того ж файлу, то

замість цього ми отримаємо наступне:

ВИХІД

2

6

10

19

22Поясніть, чому -n має такий ефект.

Опція -n задає числове, а не алфавітно-цифрове

сортування.

Ми також використовуватимемо опцію -n, щоб задати

числове сортування замість алфавітно-цифрового. Це не змінить

файл; натомість відсортований результат буде виведено на екран:

ВИХІД

9 methane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

20 cubane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

107 totalМи можемо записати відсортований список рядків в інший тимчасовий

файл з назвою sorted-lengths.txt, додавши

> sorted-lengths.txt після команди, так само як ми

використовували > lengths.txt, щоб записати вивід

wc у lengths.txt. Потім можна скористатися

командою head, щоб отримати перші кілька рядків у

sorted-lengths.txt:

ВИХІД

9 methane.pdbВикористання -n 1 з head вказує команді, що

нам потрібен лише перший рядок файлу; -n 20 поверне перші

20 тощо. Оскільки файл sorted-lengths.txt містить довжини

наших файлів, впорядковані від найменшої до найбільшої, виведенням

head має бути файл з найменшою кількістю рядків.

Що означає >>?

Ми вже розглядали оператор >, але ще існує схожий

оператор >>, який працює трохи інакше. Ми дізнаємося

про відмінності між цими двома операторами, надрукувавши кілька рядків.

Для виведення рядків ми можемо скористатися командою echo,

наприклад:

ВИХІД

The echo command prints textТепер протестуйте наведені нижче команди, щоб виявити різницю між цими двома операторами:

та:

Підказка: Спробуйте виконати кожну команду двічі поспіль, а потім переглянути вихідні файли.

У першому прикладі з > рядок ‘hello’ записується до

файлу testfile01.txt, але файл перезаписується кожного

разу, коли ми запускаємо команду.

З другого прикладу ми бачимо, що оператор >> також

записує рядок ‘hello’ у файл (у цьому випадку

testfile02.txt), але додає рядок до файлу, якщо останній

вже існує (тобто, коли ми запускаємо його вдруге).

Додавання даних у кінець файлу

Ми вже знайомі з командою head, яка виводить рядки з

початку файлу. Команда tail схожа на неї, але виводить

рядки з кінця файлу.

Розглянемо файл

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/animal-counts/animals.csv.

Після виконання цих команд оберіть відповідь, яка відповідає вмісту

файлу animals-subset.csv:

- Перші три рядки файлу

animals.csv - Останні два рядки файлу

animals.csv - Перші три рядки та останні два рядки файлу

animals.csv - Другий і третій рядки файлу

animals.csv

Варіант 3 є правильним. Щоб варіант 1 був правильним, потрібно

виконати лише команду head. Щоб варіант 2 був правильним,

нам слід виконати лише команду tail. Щоб варіант 4 був

коректним, нам слід передати вивід команди head у команду

tail -n 2 виконавши

head -n 3 animals.csv | tail -n 2 > animals-subset.csv

Передача виводу іншій команді

У нашому прикладі для пошуку файлу з найменшою кількістю рядків, ми

використовуємо два проміжні файли lengths.txt та

sorted-lengths.txt для зберігання результатів. Такий підхід

може збивати з пантелику, оскільки навіть зрозумівши як працюють

wc, sort і head, ці проміжні

файли ускладнюють відстеження всього процесу. Щоб легше було зрозуміти,

можна одночасно виконати sort і head:

ВИХІД

9 methane.pdbВертикальна риска | між двома командами називається

каналом (pipe). Вона вказує терміналу, що вивід команди

ліворуч слід використати як вхідні дані для команди праворуч.

Це усуває необхідність у файлі sorted-lengths.txt.

Поєднання декількох команд

Ніщо не заважає нам з’єднувати канали послідовно. Наприклад, ми

можемо надсилати вивід wc безпосередньо до

sort, а потім результат — до head. Це усуває

необхідність у будь-яких проміжних файлах.

Ми почнемо з використання каналу для надсилання виводу

wc до sort:

ВИХІД

9 methane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

20 cubane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

107 totalПотім ми можемо передати цей вивід через інший канал до

head, отже повний конвеєр буде мати наступний вигляд:

ВИХІД

9 methane.pdbЦе подібне тому, як в математиці ми розглядаємо складні функції на

кшталт log(3x) і кажемо ‘логарифм трьох x*’. У нашому випадку,

обчислюється ‘head від sort від підрахунку кількості рядків у файлах

*.pdb’.

Перенаправлення та канали, використані в останніх кількох командах, проілюстровані нижче:

З’єднання команд у конвеєр

У нашому поточному каталозі ми хочемо знайти 3 файли, які мають найменшу кількість рядків. Яка з наведених нижче команд підійде для цього?

wc -l * > sort -n > head -n 3wc -l * | sort -n | head -n 1-3wc -l * | head -n 3 | sort -nwc -l * | sort -n | head -n 3

Варіант 4 є рішенням. Символ каналу | використовується

для під’єднання виводу однієї команди до входу іншої. Символ

> використовується для перенаправлення стандартного

виводу до файлу. Спробуйте це у каталозі

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/proteins!

Інструменти, створені для співробітництва

Представлена вище можливість комбінування програм є причиною успіху

Unix. Замість створення величезних програми, які намагаються робити

багато різних речей, розробники Unix зосередилися на створенні численних

простих інструментів, кожен з яких добре виконує одну роботу і при цьому

чудово взаємодіє з іншими. Ця модель програмування називається ‘канали

та фільтри’. Ми вже бачили приклад каналів; а

фільтри — це програми на кшталт wc або

sort, які перетворюють потік вхідних даних у потік

вихідних. Майже всі стандартні інструменти Unix можуть працювати таким

чином. Якщо їм не вказано робити інше, такі програми читають дані зі

стандартного вводу, виконують з ними певні дії та записують результат у

стандартний вивід.

Головне полягає в тому, що будь-яка програма, яка зчитує рядки тексту зі стандартного вводу і записує їх у стандартний вивід, може бути об’єднана з будь-якою іншою програмою, яка працює так само. Ви можете і повинні писати свої програми таким чином, щоб ви та інші люди могли з’єднувати їх через канали і тим самим суттєво збільшуючи їхню потужність.

Розуміння роботи з каналами

Файл з назвою animals.csv (у каталозі

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/animal-counts) містить

наступні дані:

2012-11-05,deer,5

2012-11-05,rabbit,22

2012-11-05,raccoon,7

2012-11-06,rabbit,19

2012-11-06,deer,2

2012-11-06,fox,4

2012-11-07,rabbit,16

2012-11-07,bear,1Який текст проходить через кожен із каналів та фінальне

перенаправлення у конвеєрі нижче? Зауважте, що команда

sort -r сортує у зворотному порядку.

Підказка: створюйте конвеєр по одній команді за раз, щоб перевіряти своє розуміння

Команда head виділяє перші 5 рядків з файлу

animals.csv. Потім останні 3 рядки виділяються з попередніх

5 за допомогою команди tail. За допомогою команди

sort -r ці 3 рядки сортуються у зворотному порядку. І

нарешті, результат перенаправляється до файлу final.txt.

Вміст цього файлу можна перевірити, виконавши команду

cat final.txt. Файл повинен містити наступні рядки:

2012-11-06,rabbit,19

2012-11-06,deer,2

2012-11-05,raccoon,7Конструювання каналу

Для файлу animals.csv з попередньої вправи розглянемо

наступну команду:

Команда cut використовується для видалення або

‘вирізання’ певних частин кожного рядка у файлі. Вона очікує, що рядки

буде розділено на стовпчики символом Tab. Символ, який

використовується таким чином, називається роздільником.

У наведеному вище прикладі ми використали опцію -d, щоб

вказати кому як роздільник. Ми також використали опцію -f,

щоб зазначити, що ми хочемо вилучити друге поле (стовпчик). Це призведе

до наступного результату:

ВИХІД

deer

rabbit

raccoon

rabbit

deer

fox

rabbit

bearКоманда uniq відфільтровує сусідні однакові рядки у

файлі. Як можна розширити цей конвеєр (за допомогою uniq та

інших команд), щоб з’ясувати, назви яких тварин містяться у файлі (без

повторень у їхніх назвах)?

Який з каналів використати?

Файл animals.csv містить 8 рядків даних, відформатованих

наступним чином:

ВИХІД

2012-11-05,deer,5

2012-11-05,rabbit,22

2012-11-05,raccoon,7

2012-11-06,rabbit,19

...Команда uniq має опцію -c, яка підраховує

кількість разів, коли рядок зʼявляється у вхідних даних. Припускаючи що

ваш поточний каталог має назву

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/animal-counts, яку команду

слід використати, щоб створити таблицю у файлі з підрахунком загальної

кількості тварин кожного типу?

sort animals.csv | uniq -csort -t, -k2,2 animals.csv | uniq -ccut -d, -f 2 animals.csv | uniq -ccut -d, -f 2 animals.csv | sort | uniq -ccut -d, -f 2 animals.csv | sort | uniq -c | wc -l

Варіант 4. Це правильна відповідь. Якщо вам важко зрозуміти, чому,

спробуйте виконати команди або фрагменти конвеєру (перед цим

переконайтеся, що ви перебуваєте у каталозі

shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/animal-counts).

Конвеєр Неллі: перевірка файлів

Неллі обробила свої зразки в аналізаторах і створила 17 файлів в

каталозі north-pacific-gyre, описаному раніше. Для швидкої